Review by Alicia Marie Brandewie

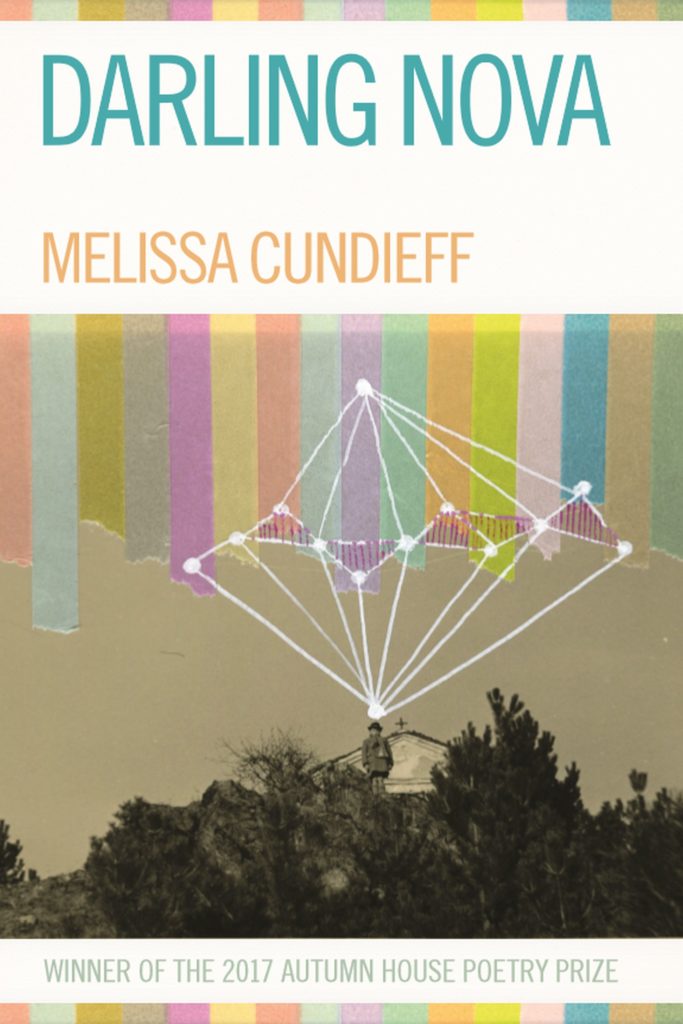

From the very title onwards, intimate affections and expansive worldviews coincide in Melissa Cundieff’s debut collection Darling Nova (Autumn House Press, 2018), winner of the 2017 Autumn House Poetry Prize. The collection encompasses from the micro level of person-to-person relationships to the macro levels of interstellar physics, sociology, and spirituality. Through regret and desire, love and haunting, and against a complex, hyper, pain-inducing world, Darling Nova asks: “do we not all have// some place more human to go?”

With the first poem, “Who Now to Rebel Against,” Cundieff dispenses with shame and its silent ravages: “I’m driving away from a childhood/ friends’ funeral. She died badly, her mother/ embarrassed and hiding the cause.” Hepatitis worsened by alcohol. The poems readily reveal bleakness and bad judgments, from friends’ mistakes to the speaker’s own. The speaker is never defensive; she never hides her own flaws, mistakes, or sins. From betraying her child by slapping away his hand in “Snakes” at the beginning of the collection to the bogeyman who she confesses everything to in “Bird of Paradise” near the end. the speaker’s implication in the humanness of trauma and the ways we wound one another makes her a credible critic of interpersonal dynamics and gives her prophetic moments credence. The opening poem rings to a close: “Reminiscence is an augury/ backwards, a slow bullet returning to us, now.”

In blistering moments of clarity on the past, future, and human nature, Cundieff commands physics, religion, folk art, philosophers, and psychology. The collection draws on references to indie singer Joanna Newsom, ‘50s film flop “The Conqueror,” critic and philosopher of language and society George Steiner, activist and mystic Simone Weil, and writer-turned-musician Leonard Cohen. Darling Nova graphs the calculus of humans to each other, the animal, and spiritual worlds with the likes of apogee, perigee, the modern curse of radiation in “The Conqueror, 1956,” and the title “Coefficient of Restitution.”

Cundieff’s linguistic calculations are as precise and powerful as the unexplainable forces of god, bardo, and magic; “gymnasium carnations burning/ our wrists down to desire” characterize adolescence in “Roll Call (2),” and “its cancer of windows flush against lace” in “Half-life” lets our society speak its own volumes about how we shun members with mental health issues. There are ways of losing and of grieving that English does not have words for, ways that it cannot bear in its abstract words of emotion—sadness, pain, indifference, grief, ambivalence, relief—but Cundieff can say with worms, matroska, cigarettes, and a dead darling “like a boy and his roan horse// off to split the warm wind/ with their teeth and chess, wet and white/ below the sun’s burst fist.”

Darling Nova’s cast of characters includes a freak, mystics, lost kings, sluts, death, imperfect mothers, God, oddballs, weirdos, poor lovers, the bogeyman, eccentrics, villains, and witches. As with any good fairy tale or myth or life, these poems are haunted: a lost pregnancy, her father’s life and death, the father’s childhood friend who abused animals, a drowned Syrian refugee toddler, a lightning-struck all-American football player, and a friend who died by suicide. Cundieff has a talent for characterization that neither sugars nor salts, letting complex relationships shine.

On the shelves of these poems are the shards, bits, blood, and relics that power priests, fairies, and physicists alike. The speaker is a conjuror, a witch, an oracle, a mystic, and a priestess. In “Rebirth” she comes back as a bird; in “West,” Cundieff writes: “this time I am dead, I died a year ago, and it’s only my afterimage/ positioned in the passenger seat.” As befitting those titles, the poems are also full of stark wisdom, like “The risk of remembering is guilt, my friends” and “The headstone names around us/ fooled you into thinking we weren’t so/ dangerously alone.” As in the Grimms’ fairy tales, there is reality in the fantastic, and there is rawness and ugliness in magic. In “Fairy Tale” the speaker is a poor witch against two boys on the playground, “two oiled and ready beasts.” who know they can hurt her just as much as the archetypal wolf and bogeyman.

The structure of the collection—one undivided string of poems—conveys how beginnings and endings are not opposite or divided; rather, they are moments that blend together in cycles and pass traits from one generation to another. The poems, like stars and memories, seem fixed, but they can be constellated differently by each reader, rebirth, generation, or mysticism. The side-by-side poems frequently link together explicitly—for example, the poem “Freak,” which begins with “Open his mouth for a word and it will be tooth,” is followed by the poem “Eyetooth,” and both poems beget a “previous life.” These clear but impressionistic connections whipstitch the collection together, although it is best to let go of both a conventional understanding of characters and the ubiquitous creative writing workshop question “What is their relationship to the speaker?” The labels, categories, and particulars of chronology and biology are not necessary here; only knowing that the characters are important to the speaker is essential.

Darling Nova exists in the bardo, in the cycles we inhabit between life and death. It asks the most human questions that science and religion also try to answer—like how do we live well after pain, or with it? The collection answers with its own mythology, lore, testaments, and table of elements: worms represent growth and potential, air and sky represent emptiness and abandonment, tooth represents food and the physical world, words/language represent the connection of all living things, and leaves abound for grief. To these essential questions, the poems reply that there are not always satisfying answers, but there are ways of pushing through the cruelties of existence. There are incantations and relationships that will pull you through.

Alicia Marie Brandewie