Jaime Zollars is a painter and printmaker. She teaches in the Illustration Program at the Maryland Institute College of Art.

***

Interviewer: Your art has a strong narrative quality—it seems you often paint scenes at their moment of highest tension, at the climax of the story they depict.

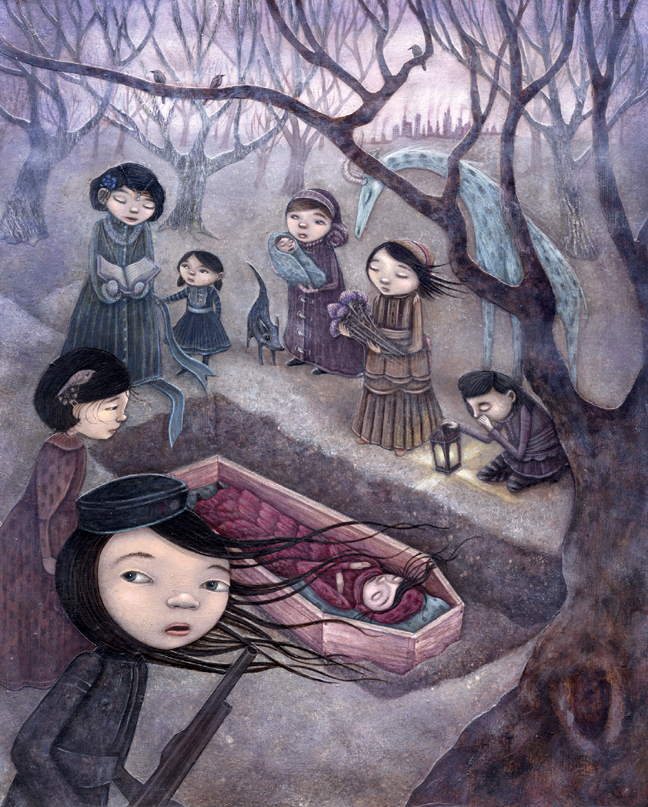

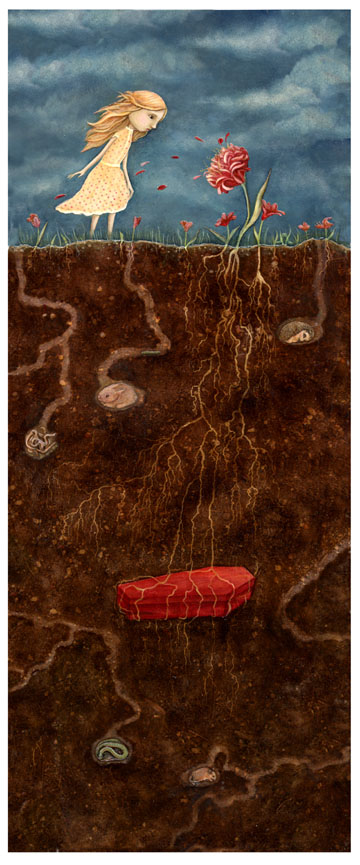

Zollars: I am definitely interested in capturing moments of tension in my work. I like to think of my personal pieces as film stills within a greater narrative. From a conceptual standpoint, I tend to know much more about each narrative than is actually pictured in the piece. My knowledge of this bigger story helps to add a specificity and depth to the work that will hopefully lure viewers in and invite them to ask questions. I try to create images that ask questions instead of answer them.

On the technical side, I strive to use color and value to create a visual hierarchy in each painting. The viewer won’t be able to recognize suspense or tension if the piece is not visually accessible. The area with the highest contrast in value generally indicates the focal point, and I use this area to pull the viewer in and quickly communicate the overarching theme and feeling of the work. Hopefully there will be enough interest in that first read to warrant a closer look and allow other elements of the image to reveal themselves.

Besides the image simply making conceptual sense, the goal of my work is ultimately to evoke an emotional response. Images that depict moments of tension are more likely to connect with the viewer in an emotional way. I use a limited palette, which helps to create a more atmospheric and believable world, even when the characters and environments are quite surreal. Using a limited palette also allows me to spike my images with small areas of more saturated color, which can be used to emphasize distinct areas of movement, noise, or climax.

Interviewer: How do you develop this “bigger story” before painting the moment of tension?

Interviewer: How do you develop this “bigger story” before painting the moment of tension?

Zollars: It really depends on the piece. Sometimes it comes easily, where I can see an image in my head that I’d love to create, and then begin by asking myself what it could mean. I sketch it out roughly, and then start to decide who the people are in the piece, why they are there, what came first, and what will happen next. I can’t say I know this much about every piece, but I try to answer as many of these questions as I can before proceeding.

But it doesn’t always come easily. Like many artists, I do feel that pressure to simply sit down in front of an empty page to produce “art” and “have ideas.” And sometimes I just don’t. When direct imagery eludes me, I set out to inspire myself. This inspiration can come from anything. Sometimes it is a flea market trip, where I seek a remarkable object and speculate from where it came. Other times I start reading a book or article that I’m interested in to help spark a vision. I cannot rely on what exists inside my head and studio alone; I soak up the world around me and see what comes of it.

Once inspired, sometimes the image comes quickly. Other times I create an epic story in my head and on paper before I have a good image in mind, with pages of notes and sketches concerning another world, place, and time. Then I seek a pivotal moment within the context of my new world and its people and start drawing from there.

I don’t have a concrete method for conceptualizing, which can be stressful at times. But because my painting process is very methodical technically, I recognize that without some unpredictability in my methods somewhere, my art would get stale very quickly. This element of the unknown in my process is what ultimately keeps the work interesting for me, and visually surprising for others. I figure that if I maintain interest in my own work, it is more likely to be interesting to other people. I set out to simply like what I do. I like to hope that this is the key to long-term success and happiness in what can be a fickle field.

Interviewer: It seems like some of your paintings are connected, too, and work together to form a larger narrative. Do you see the narratives in your work as being part of the same world?

Zollars: Some of my pieces are most certainly connected. I see these worlds as platforms from which to express contemporary ideas or concepts that may have been more easily dismissed if they were set in our world. I like to think that these larger worlds exist somewhere and that the residents of these places must face similar issues that exist in contemporary society. If I can revisit any bits and pieces to successfully convey the idea at hand, I will. I do intend each image to be an individual story, but hopefully without being disruptive to a potentially larger one.

That said, sometimes I do create works in a series for larger or solo shows, and these ideas are usually born from a specific piece where I see the potential for a larger story. My show titled “Melancholia” (at CoproNason gallery in Santa Monica) began by revisiting a piece I had done a year prior, “Important Visitor.” “Important Visitor” was an image from another world: a line of inhabitants carrying prized possessions and resources to sell off from their colorful world. My “Melancholia” series was a flash forward to what that world would become, and continued that story through a new set of works.

Interviewer: Which stories do you see as influences on your art?

Interviewer: Which stories do you see as influences on your art?

Zollars: Fairy tales and folk tales from around the world. I have shelves of books of these stories, and initially my pictures were interpretations of pivotal moments in them. I am trained as an illustrator, so I initially set out simply to bring these written words to life. In college, I was especially fascinated with Grimm’s Fairy Tales and how they had changed and adapted over the years. I was intrigued by how dark the initial stories were. I started painting those lesser known moments, and realized quickly that there were no commercial venues for this work. When I turned to galleries as an outlet for the paintings I simply wanted to create, I realized that I no longer had to illustrate existing text, and started to mesh the familiar feeling and fantasy of these beloved tales with my own concepts and ideas.

While fairy tales and the storybook genre will always have a place in my work, most of the inspiration for my current imagery comes from reading a lot of nonfiction: I’m currently reading a book on the history of North Korea, a book on the secret world of fine art, and one about the historical relationship between science and religion.

When I’m painting, I also like to listen to songs that strike an emotional chord with me. I do not believe any of my content is driven by music, but I strive to achieve an emotional reaction to my paintings in the same way that I can feel an emotional connection to great music. Art has the most impact when it can make us think and feel, and I believe that is a worthy (if ambitious) goal. At this very moment in my music queue: The Eels, Arcade Fire, and Kadman.

While I see film as an amazing opportunity for art as well, my work is not specifically driven by film. On the rare occasion I have the chance to watch the television these days, you’ll find me tuning in for Flight of the Conchords on DVD, 30 Rock, Saturday Night Live (for its occasional moments of brilliance) or Parks and Recreation. This is a definite break from and contrast to my art, but sometimes a bit of smart and creative humor helps keep me sane.

Interviewer: Are there any fairy tales you find yourself being drawn to again and again?

Zollars: Hans Christian Andersen’s “The Snow Queen”—not necessarily for the story, which is on the more interesting side of traditional storybook fare, but for some of its visuals. Otherwise, I like mixing it up and collecting inspiration from various sources.

Interviewer: Did you read any comics growing up?

Interviewer: Did you read any comics growing up?

Zollars: Actually I did not, but I wish I had discovered that world at a younger age. I have only recently discovered the genre, and have enjoyed attending San Francisco’s Alternative Press Expo, Bethesda’s Small Press Expo, and San Diego’s Comic-Con over the past few years. I left the Small Press Expo this year with a bunch of Chris Ware stuff, Lilli Carre’s Woodsman Pete, Esther Watson’s Unlovable, Aaron Renier’s Spiral-Bound, and Guy Delisle’s Pyongyang.

Interviewer: It’s interesting to compare your work to someone like Ware’s; whereas Ware is using a series of images with text arranged sequentially to tell a story, your paintings are telling a story just with just that one image. And although your prints don’t use text as part of the actual image, the titles of your images often do some of the storytelling work—they shift our understanding of the narrative, change how we understand the story.

Zollars: Well, I’d like to think that is all true. And any comparison to Ware is more than welcome. Ware was my introduction to the graphic novel. Smart but playful, colorful but sophisticated, detailed but not overwhelming, and stylized but full of emotion, Ware has to be my favorite artist in the genre. I stumbled upon him while looking for paper art to include on my PaperForest blog. When I found his lovely paper model work, I was instantly hooked. I had the opportunity to see his original work at the Masters of American Comics show at MOCA a few years ago, and it met the almost impossible standard I’d created for him and his work.

As for my own work, I’d love to achieve this balance of play and sophistication, and I constantly strive to become a better storyteller. I do try to use the titles of my work to shed some light on the intended meaning of each piece, because it is one of the few bits of control I have over their interpretation. Ware and other talented folks do make me secretly want to try my hand at the comic format, but I feel intimidated by writing and the craft itself. Plus I’d probably want to paint each panel in the same style as my paintings, and that is not exactly a realistic goal. I fear I’m not quite fast enough for the graphic novel genre—I think I was meant simply to appreciate it.

Interviewer: How do you arrive at your title for each piece?

Interviewer: How do you arrive at your title for each piece?

Zollars: Some of the pieces I’m sketching right now have names already, before I’ve even started painting, and those names will shape the pieces themselves. This is more likely to happen in the case of a series, where the pieces connect and are constructed as a set.

In most cases though, a title comes to me while I’m painting as a response to the image, sometimes filling in gaps of meaning. Many times it comes from what I’ve written down before beginning the piece. Since my research involves writing and brainstorming words, those which have stood out in that process are generally circled, and I come back to those words if I need to. My “Red Bird Battalion” piece was for a show titled “Bergamot Invasion,” referring to the gallery complex and the fact that a new type of gallery was moving in. So I started brainstorming ideas for my painting with the theme of “invasion” and wrote down a set of words that came to mind. “Battalion” was a favorite. At the time, I had a bird obsession (which I guess I still do), so “Bird Battalion” was an inevitable pairing of words and a great start to my image. And the “red” became obvious after the painting was complete.

Other titles were needed to explain something that may not be evident in the piece or that will help people to research the piece (if there is information to be found). Calling my first ninja piece “Tengu” was just enough to have people looking up that unfamiliar word, and gleaning more insight to the painting.

Interviewer: What’s your process like?

Zollars: As far as the technical process is concerned, I start with a bunch of tiny little thumbnail drawings, until one really seems to stand out. Then I scan that tiny thumbnail, blow it up, and print it out. I put vellum paper on top and draw a more detailed sketch on top. I have found that this allows me to keep the proportions and impact of that initial drawing better than if I decided to simply redraw it at a larger size. Sometimes I repeat this process with the new drawing, scanning it and adding even more detail, but not always. I do always use one of those blue lead holders, sharpened quite often. Once I discovered these and found out that my pencil really never had to break again, I never went back.

I’ve learned over time that although a color study usually feels like extra work at the time, figuring out one’s palette before moving to final work is key and saves way more time in the long run than not doing a study. So that is next. I actually do that in the computer now, so that I have more flexibility in being experimental with color.

Once I have my color study, I go on to the final piece. I sometimes paint directly over an archival print of the study, just so I can see the colors before I cover them and revise the image with my own paint. Other times, I start with a transferred drawing or collage elements. I like to work on Illustration board, but I am moving towards wood for gallery work. I paint in Acrylic, and finish most pieces with Galkyd, an oil-based Varnish. This varnish alone tends to make some people think my paintings are oil. And it gives a rich, buttery vintage color to the piece.

Because my painting process is quite slow and methodical once my color is in place, I often need a bit more stimulation than music provides, so I generally like listening to NPR shows or audio books while painting, just to keep my seat in my chair. Otherwise, I’m a wanderer. Food requirements are simple: non-fat latte (sometimes iced) and something sweet to go with it. If I don’t have any sweets, I’ve been know to walk to grocery store just to satisfy such an urge. If there were a cupcake shop across the street, I could keep it in business, so it’s probably good that there is not.

Interviewer: How do you balance your art with teaching and your family?

Zollars: I’ve been married for eleven years, and I have a two-year-old son. If I’m being completely honest, I’d say I don’t balance it all very well just yet. I try to stress this when others in my situation seem frustrated that I’m able to “do it all” when they find that difficult for themselves. I generally say that they probably have their priorities a bit more straightened out than I. But I’m working at figuring that all out for myself.

I love my work (sometimes perhaps more than I should) and my schedule reflects this. On days that I don’t teach, I wake up before seven a.m., get my toddler ready for school, take him to school, and come back home to work. The bulk of my day consists of balancing multiple projects at once. Aside from teaching two days a week during the school year, I’m currently working on advertising work for United, drawing for my next kid’s book, helping to edit and jury a paper arts book, participating in indie art shows across the country, serving as Programming chair for ICON6 (a big, amazing illustration conference in Los Angeles this summer), and I’m working on pieces for a show coming up in July at Gallery Nucleus. On a daily basis, I am usually on at least two work-related calls, have fifty work e-mails that need responses, and have to address contracts and do other administrative tasks. Then I must somehow find time to actually create new work!

When I pick up my toddler at around five p.m., we spend some time together, have dinner, do the bedtime rituals, and then I’m back up in the studio until the wee hours of the morning. Last week I averaged about three hours of sleep a night, sneaking in seven one night because apparently that sort of schedule is unsustainable. If I need to go to an occasional weekend show or out of town ICON meeting, my in-laws live about an hour away and are happy to take their grandson here and there; we are so lucky to have them nearby! In some ways it is good that my husband works all the time, because it facilitates my being able to work a lot too. Though perhaps if he weren’t so busy it would force me to have a bit more life balance.

The amazing part about being an illustrator is the flexibility you have to do things other working people cannot. I can work from a coffee shop midday for a change of pace, I can go to my son’s school early, or take a day off to visit a friend. But because I always have work that I could be doing, and I work from a home studio, I am never actually “off” of work like normal people with normal jobs. I feel compelled to work all of the time because I live where I work, and have a hard time shutting down my computer or my “work mode.”

I’ve also historically taken most jobs that have come in, a habit many freelancers continue to do for too long, but now I’m starting to be more selective, only taking on pet projects and those I really like.

Interviewer: What’s your experience been like in Baltimore, after working as an artist in L.A. for so many years?

Zollars: When I found out my husband got his first choice residency at Johns Hopkins and we were moving to Baltimore, I was honestly underwhelmed. It was really one of the last places I had wanted to live. I was hoping for Seattle or for staying in Los Angeles—his other top choices. I started taking daily inventory of all the things I would miss in Los Angeles, and there were many things: being around Art Center [College of Design] and the talented people I met there; gallery culture and resources; the cosmopolitan polish of such a big city. Baby Griffin would come along the following week, and I just didn’t seem ready to make an impossible move across the country.

My husband went to Baltimore for a week to find a place to live. To our surprise, Baltimore was affordable enough that we could actually buy a house in the city, just blocks from the harbor. We were going to live in Fell’s Point, amidst great restaurants, shops, and parks. Eric was going to be able to walk to work. I would have places to walk outside and explore easily with my two-month-old baby in tow. And when we went walking, the neighbors were interested in us. The people were very friendly and direct, and I got to know more of them within two weeks than I did in two years in Los Angeles. The sense of community in Baltimore is palpable and wholly authentic. What Baltimore lacks in the gloss of Los Angeles, it makes up for in its authenticity. The row homes and shops have past lives, neighbors join forces to buy and save buildings and maintain local resources. I realized that unlike L.A., these people are not just passing through on their way to the top—they are building something together for the future.

My experience at MICA has turned me on to the talented artists that work and live in this city, a city that most outsiders know little about. Baltimore has quirk and style, some pretty great museums, including the American Visionary Art Museum (a must-see), and an emerging art and music scene. I cannot pretend that I don’t miss the weather and amazing gallery scene already in place in Los Angeles, but the talented students I’ve taught who plan on sticking around are a promising sign that this city is on the cusp of being known for its own distinct artistic vibe.

Interviewer: What first got you painting?

Interviewer: What first got you painting?

Zollars: I actually painted very little in high school, but that was where I began to experiment with media beyond a pencil and paper. I felt pressure to graduate from colored pencils, but remember being completely thrown off by paint. My instructor would give me A’s on all of my drawings and C’s and D’s on my paintings. (It was a pretty demanding AP class.) He always wanted to know: how could I draw so well, but have no concept of how to paint? This was frustrating, and I thought I’d never find success in painting.

Five years later, I took an Illustration class with Rob and Chris Clayton at Art Center College of Design. They showed us the specific acrylic paints they liked to use (Liquitex Concentrated Artist Colors in the little bottles). This was the first time I’d taken a specifically illustration-based class at a college level, and I decided to focus all of my energies on the goal of creating successful imagery with paint. I sat and stared at the illustration board for hours, and spent way too much time with every square inch of it, but by the end of the class, I had cracked the code for myself. I began using wet media like the dry media I was comfortable with, using dry-brush layers of paint to achieve the gradations in my work. I was by no means a painter yet, but could conceivably get the image on the paper to look somewhat like what I wanted, and this gave me the control and confidence I needed to pursue the full-time program at Art Center that fall.

Interviewer: Had you been working in an art-related field in the interim?

Zollars: A lot of things happened for me between high school and the Art Center.

I actually have two undergraduate degrees. Out of high school I went to the University of Maryland, Baltimore County. I was offered a full-scholarship with room and board, and at the time that was difficult to pass up. I ended up majoring in photography, and even ended up with a fashion photography internship in New York City.

But while at UMBC I found myself crafting my own sets, painting my own backdrops, and “illustrating” scenes before photographing them. I was challenged by my instructors as to why I needed photography at all in my work, and I started thinking about creating art for the entertainment industry. I began researching grad schools, but found that I still really needed the level of technical instruction emphasized in strong undergraduate art programs. Once I decided to choose my school based on the skills I would leave with in lieu of a specific piece of paper, Art Center was an easy choice for me, and I headed West.

When I first moved out to California, I landed the job of Art Director for a very small company that designed menus for all kinds of restaurants. I did all of the design and artwork for them, but was very underpaid. I knew I had to either apply Art Center or most likely settle for a job outside of art. So I signed up for my first night course there to build my portfolio, an introduction to environmental design. That class didn’t go so well.

My final critique in environmental design was by far the worst I’ve ever experienced. The instructor and the guest critic hated everything I had done. I believe their exact words were, “I really hate this, and see no redeeming qualities in it.” Then they decided they would tell me all of the specific things they hated about it and why. They were bluntly harsh. The only thing they liked about my concept hotel model was that I used Craisins to fashion tiny palm tree fronds on the ends of delicate dowels. It was the only time I ever completely broke down in a critique: to make matters worse, my husband had come up with the Craisins idea, effectively rendering me useless. (This point is somewhat funny now, but hardly so at the time.) I was a mess. The next morning I was completely lost. I felt I had moved to California to become something that I wasn’t talented enough to become.

Then I signed up for that night class with the Clayton brothers, and things really changed for me. They were very supportive and encouraging and excited for me, and told me I really needed to come to Art Center and pursue this. The morning after that final critique I was the opposite of lost. I could not wait to jump in and become an illustrator. I applied that summer and started in the fall.

Interviewer: Do you think the blunt, brutal critique can ever be helpful? How do you run the critiques in your own courses—how do you criticize a student’s work without leaving them feeling lost?

Interviewer: Do you think the blunt, brutal critique can ever be helpful? How do you run the critiques in your own courses—how do you criticize a student’s work without leaving them feeling lost?

Zollars: This is a good question, and I can’t say I have a concrete answer for you.

In my case, you could say that if a harsh critique so easily turned me away from pursuing environmental design, then I wasn’t passionate enough about it to be successful. And if I had taken those critical words and used them as ammunition to outperform my peers, it could have been the impetus for my success.

Alternatively though, it may have simply been an unfortunate case, where I just was not ready to process what was being dealt. I did not have the experience to understand that this critique was about this particular project, not my ability to become a designer. At that time, I certainly did not know how to use it to make myself better. It was an intro class, after all.

We all have moments when we are unsure of our ideas. At times I still feel vulnerable expressing my own ideas because good ones can be personal, new, and risky. So you can be sure that students are even more afraid that theirs aren’t good enough. The greatest ideas are often the ones we are afraid to share because they break the mold—they might feel silly to express. I want students to get those ideas out, so I try to keep the classroom relatively casual, in order to help support and facilitate sharing. In school, I remember throwing my fringe ideas out before I stepped into the classroom and honing in on the ones that felt safe and predictable. I don’t want the same for my students.

That said, I don’t hold back on my opinions. The art form of the critique is in the delivery of those opinions. I believe that my goal as an instructor is to get the best work possible out of each and every student (while maintaining their own personal vision, not mine). And since each student is different, I believe that I critique each in a slightly different way. I do not believe there is a formula for a successful critique. Some students are at the point where they just need to know if they are moving in the right direction, and others are ready to open the floor to intense scrutinization and debate. So ideally I’d hit the right amount of criticism to motivate new and better work while avoiding a defensive reaction. And this sweet spot is different for each student. I don’t always get it right, but I always try.

There are times when I think that the harsh critique is useful. If you are ready for it emotionally, difficult questions are important to face in order to grow as an artist. But you have to enter a critical room with some roots planted first. You need to have some understanding of who you are as an artist before facing the storm, so that the personal core of your work survives. Students enter art school quite vincible. They pick up on the negative words right away, and simply forget about the positive ones. When feeling threatened, many are quick to abandon their own artistic instincts in order to emulate the art that others are making, or to create the art they think that they should be creating. This is usually motivated by the fear that their own unique vision will not surface or suffice. Students feel too much pressure in school to trust themselves and wait it out. This happened when I went to school, and it happens now more than ever. I can’t stop my students from feeling pressure or being threatened by competition (and some of this is healthy), but I can try to make students aware of the unique parts of their work that they may not be able to see right away for themselves. I start a critique by asking the question, “What is working in this image?” followed by, “What can I do better next time?” This will at least establish the redeeming qualities of the work before deciding what problems need to be addressed.

I see the critique as a perpetual experiment in uncovering a balance of responsibility, motivation, and personal growth in each student, an art to itself that I hope to refine each term that I teach.

Interviewer: Lynda Barry has written that, after she already had been established as a successful artist and writer, she became haunted by the questions “Is this good?” and “Does this suck?”; she couldn’t sit down to draw or write without being subjected to this ongoing critique in her internal monologue. For her it was crippling. Have you experienced anything like this—having to overcome not the criticism of your teachers or peers, but your own criticism of your work?

Zollars: Of course I question my work, and have thought it relatively worthless at times. In school and when I began creating images professionally, I would dwell on each piece, laboring over it to make it “better” until it was overworked and lifeless. I felt I could (and should) always make each image better; my art was never as good as it could be. But I think I was looking at this all the wrong way.

As a professor, I’ve gained some major insight into the process of creating. Even though I’d always looked at my own paintings as equally important autonomous works, I’m able to look at each of my students’ images as pieces of a journey. I see that each new image will be just a little bit better than the last, with a few hiccups and experiments along the way. I’ve found that if a student is struggling with a piece beyond what seems normal, it will probably never be an outstanding piece. The best work usually comes more quickly and a little bit more instinctually. The struggle will usually show in the piece. Occasionally this can be interesting, and in the context of fine art, perhaps enlightening, but it usually means it’s time to move on, forge ahead, and create your next, better piece. Seeing this from a removed perspective has allowed me to relax and accept that the current painting in front of me does not exist to serve as a direct reflection of how good I am as an artist.

Now I’m able to see each of my paintings as part of a process, and I approach my work with more momentum, eager to move forward and see what is next. Sometimes this means that I don’t live in the moment when creating my work, but it also means that I don’t have time to over think and worry about it anymore. I often find myself completely unattached to my paintings as soon as they are created, and have virtually no feelings toward them at all. I rely on the reactions of others to to know how successful a piece is communicating; within a couple of months, I’m removed enough from the image to see it clearly and cast my own vote.