Review by Alicia Marie Brandewie

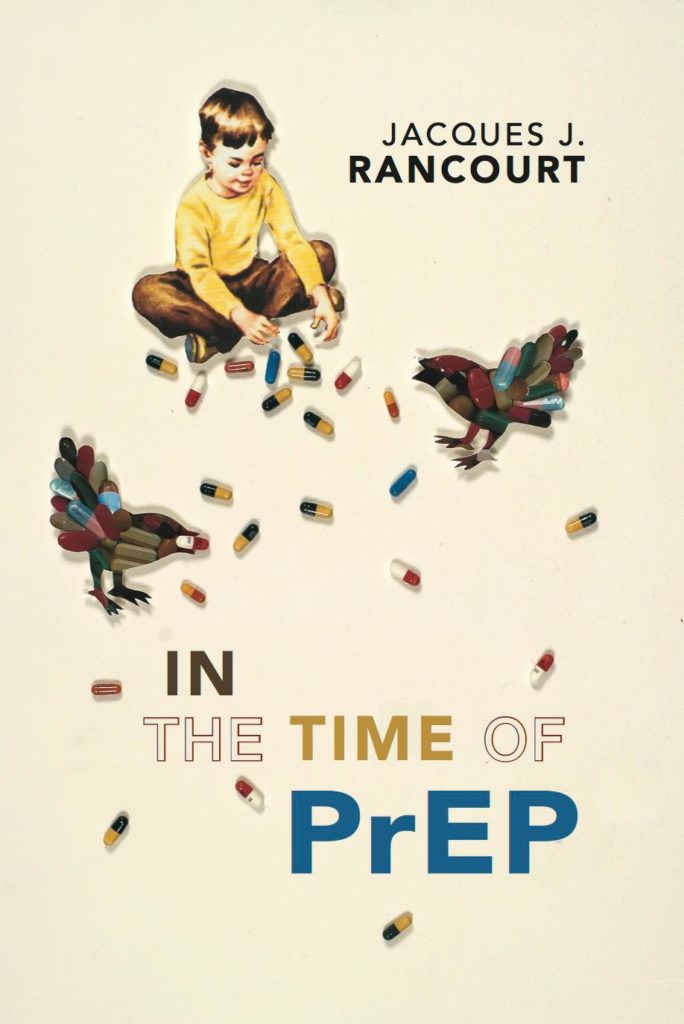

We live in different worlds, and Jacques J. Rancourt’s chapbook In the Time of PrEP (Beloit Poetry Journal, 2018) swims through several of these worlds. In gay and queer worlds, PrEP is as well known as chemotherapy, yet for those outside of gay and queer world, PrEP is not. Rancourt foregrounds the queer world but provides for the other audience. The title proem “Love in the Time of PrEP” introduces readers to a dorky husband and a “melodramatic poet” who contemplate hauntings before spooning in bed, and notes that “PrEP stands for pre-exposure prophylaxis, a pill taken daily to reduce the chances of HIV infection.” As a gay man who came into sexuality after the advent of preventative medication for HIV and maintenance medications for AIDS, the poet wrangles with how to navigate survivor’s guilt, generations of trauma, and legacies of wounds.

The chapbook is both a dirge and an exhalation. The poems are wrought with grief over the ravages of the AIDs epidemic—both the 636,000+ lives lost to death and the hundreds of thousands, if not millions, more destroyed by social, political, religious, and medical stigma and bigotry. The poems are also a celebration of how queer intimacy has survived and thrived. There is delight and recognition of history in the line, “Because we live// in the easy century,/ today we say/ our wedding vows.”

In the Time of PrEP seamlessly marries biblical references with current cultural touchstones and literary moments, and it puts the queer side of all three at the forefront. The healing pool of Bethesda is “thrashed & cut// through like a sash/ by a man standing/ naked in the center.” The 1990 photograph of David Kirby dying and his father is an “Ohio/ Pietà.” Dickinson’s Death horse “blazed/ through here & did not stop for me,” and the speaker admitting, “I was careless, yes, & spared.” There is lust and sex here, as in a great majority of literature. There is no blame in the poem “The Fall” for Eve or the younger hookup because “I want what/ everyone wants,” and “There is no deep enough.” We want, we need, to be vulnerable with people—physically and emotionally, with our partners and our society. We need deep connections.

Veiling over the poems is a fog—both the literal fog around volcanoes, which causes the Brocken specter phenomenon and shrouds wedding nights, and the figurative fog of the fear of the AIDS epidemic, still hazing our skies today. Through both, Grace Cathedral “must/ have looked, as it still looks, coming out” gloriously every morning in San Francisco. Rancourt’s images are precisely wrought and beautiful, and they do a graceful job of incorporating lust and sexual language without diminishing their rawness or going for shock value. Like in the bathhouse, “where the jizz drifting like smoke/ through the Jacuzzi is holy.”

Rancourt is also deliberate in regenerating the Christian God of his youth “that smote, in a battle over/ morality” into a spirituality that celebrates queerness and humanity. The speaker is not going to sculpt a votive like the people of Florence who commissioned Ghiberti to sculpt doors “as a way to say Thanks be to God/ we made it out almost alive, only splintered,/ only for a brief time gutted.” Instead, here is “another queer couple// making out on a bench & some days/ it seems we’ve found it a holy city// swollen with light & sound.” However, he is celebrating that he and his husband are no longer plagued by fear: “had we been// born twenty years/ back, we might be/ counted among// the dead.”

Rancourt highlights how far queer people’s rights and society has come, but also shows us how much further we still have to go. Although there are few young men “across the street hobbling// with a cane and pink bathrobe” today, the speaker and we must follow the command in the poem “Lot’s Wife” to “look now, back to where/ your people are dying.// You, most of all,/ must look.” Because there is no guarantee that this forward momentum will continue in the future; in fact, Rancourt’s speaker declares that “I know it won’t last” because “I’ve read// every myth.” We will slip back if queer people do not stay vigilant and the general population turns apathetic. In a time when being queer is still a death sentence for many, and unfiltered, rapid-fire characters can re-chart politics, every piece of art that celebrates and reveres queerness is a prophylaxis against the disease of hate.