The Role of Generational Status in Access to Mental Health Care and Quality of Mental Health Among First and Second and Later-Generation Asian Indians in the U.S.

ABSTRACT

Wide disparities within the mental healthcare industry currently exist because of a myriad of factors, the most prominent of these being cultural factors. Such individuals that retain these cultural factors include Asian Indian immigrants to the U.S. However, there are substantial differences between first-generation Asian Indian immigrants, who are foreign-born individuals, compared to second-generation Asian Indian immigrants who have at least one foreign-born parent, and third-generation Asian Indian immigrants, who are U.S. native citizens who have parents who were also both born in the United States. More specifically, first-generation Asian Indians are more likely to retain their native cultural values compared to second and later generation Asian Indians, who may be conflicted by both the American and cultural values of their parents. Therefore, this study aims to use original self-reported quantitative survey data to discover how the different mindsets, lifestyle, and interaction between first, and second and later-generation Asian Indians affect their access to mental healthcare and quality of mental health. Overall, these results statistically support that the majority of second and later-generation Asian Indians reported lower mental health ratings, higher numbers of barriers in seeking mental healthcare, higher numbers of mental health symptoms, as well as reported higher rates of feelings of discouragement in seeking mental healthcare compared to first-generation Asian Indians.

INTRODUCTION.

As mental health plays such a critical role in an individual’s well-being, mental illnesses are found to be the most prevalent health issue among U.S. residents and citizens, as 1 in 5 U.S. adults live with a mental illness [1]. Unfortunately, there are a myriad of barriers that a person may face while attempting to seek adequate mental health treatment such as public stigma, cultural values, lack of education and awareness, high cost of mental health services [2]. Moreover, wide disparities within the mental healthcare industry currently exist because of many different factors, but mostly cultural values.

Such distinctive cultural beliefs as practiced by certain ethnicities critically shape low usage rates of mental health treatment among individuals of these ethnic backgrounds. Studies have found that mental health professionals are not equipped with the proper resources to work with all individuals of diverse backgrounds [3]. The most prominent individuals who hold these possibly conflicting cultural values are immigrants to the U.S., and because of this, they are at a major disadvantage when seeking out mental healthcare, as confirmed by numerous studies [4].

Such groups with conflicting values include Asian Americans, however, Asian Indians have been shown to be an exception within the various ethnic groups of Asian Americans and the general population [5]. Multiple studies have backed up this exception in many ways, as Asian Indians are proven to have distinct cultural values (Hindu beliefs and relics) that shapes their mental health as a whole [6]. Nonetheless, there has been little research to confirm the potential barriers to seeking mental health care and the role generational status may play in specifically Asian Indians [7]. To define what each generation immigrant is, first-generation immigrants (first-generation) are identified as “individuals who are foreign-born,” second-generation immigrants (second-generation) are U.S. native citizens that have “at least one foreign-born parent,” and third-generation immigrants (third-generation) are U.S. native citizens who have parents who were also both born in the United States [8].

Current research has evaluated the barriers to mental health treatment that may exist in various ethnic groups (in Rwanda specifically), finding that fear of stigmatization, lack of awareness about mental health, cultural barriers, and financial barriers are among the most prominent [9]. Further research regarding specifically Asian Indians has also discovered that there are higher rates of cultural and mental conflict in second-generation Asian Indians compared to first generation Asian Indians [10]. There has also been research portraying specifically how immigration status (and not generational status) has affected the quality of lives of Asian Indians in the U.S.; Asian Indians already established in the U.S. are found to have a higher quality of life compared to Asian Indian immigrants currently going through the difficulties of the immigration process [11]. However, there has been very little research, if any, combining both topics—that specifically confirms how generational status, while considering 3rd generation and on Asian Indians, affects the barriers to seeking mental health treatment and quality of mental health among Asian Indians.

This study intends to bridge this research gap and establish a correlation between both generational status and barriers to mental health treatment as well as mental health quality among Asian Indians in the United States. With the online survey that study participants filled out, I attempted to learn more and observe if 1) first-generation Asian Indians would identify more barriers to seeking mental healthcare than second and later-generation Asian Indians, 2) if second and later generations of Asian Indians would identify a higher number of mental health symptoms, 3) if the majority of second and later-generation Asian Indians would report lower mental health ratings, and 4) if first-generation Asian Indians would be more discouraged from seeking mental healthcare and have lower rates of success in seeking mental healthcare.

MATERIALS AND METHODS.

Survey Design.

The survey that was distributed is very similar and inspired by a previous study that tested the barriers to mental health care in Rwanda by Muhorakeye & Biracyaza [9]. The 70 participants (all residents of various regions around the United States and either identified as first generation or second and later-generation Asian Indian) all filled out a digital survey consisting of 18 questions. The first portion of the survey consisted of 12 questions regarding the respondent’s demographic information. The 13th and 14th question asked participants to rate their mental health on a scale from 1-5, with 1 being poor and 5 being excellent, and to select any of the feelings they have felt pertaining to mental health. The 18th question also asked respondents to identify any (or multiple) of the 8 barriers listed to seeking mental health treatment, and the rest of the questions (15th, 16th, 17th) asked respondents their perceptions about seeking mental healthcare.

Data Collection.

This survey was disseminated using Asian Indian Facebook groups, survey emails, direct messaging, and in-person inquiries at Asian Indian events to recruit all of the survey participants. Before filling out the survey, respondents consented to their participation in the survey, its purpose, and assured confidentiality and anonymity within the research study by filling out a human consent form.

Data Analysis.

The data collected from the responses were analyzed using Chi-squared tests and correlational matrix tests among and between statistical variables to test how significant the relationships or correlations were between the variables. The median, Interquartile Range (IQR), minimum, and maximum values of the numerical data were also calculated to compare some of the results between the first, and second and later-generation Asian Indians (i.e. number of barriers identified and number of mental health symptoms). Lastly, I used frequency tables to see the percentage of participants in both generational statuses that identified each mental health rating (i.e. one to five).

RESULTS.

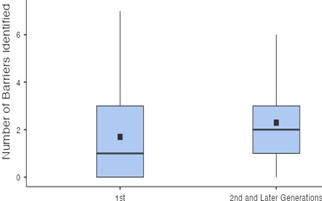

To test the first hypothesis, I wanted to discover if first-generation Asian Indians were more likely to identify more barriers compared to second and later-generation Asian Indians. The barriers/choices that individuals could identify were 1) “Lack of awareness of available mental health services and mental health professionals,” 2) “Fear of stigmatization and its consequences,” 3) “Negative attitudes of society toward mental illness,” 4) “Societal, cultural, and religious beliefs in traditional healers and prayer,” 5) “Lack of available mental healthcare,” 6) “High cost of mental health services and health insurance,” 7) “Geographical accessibility to mental health services,” and 8) “Language barriers between patients and mental health services” (Table S1). Participants could also identify no barriers (Table S1). As shown in Figure 1, the observed median amount of barriers to seeking mental health care for both first-generation Asian Indians was one barrier (Min = 0, Max = 7, IQR = 3.00) (Figure 1). In second and later-generation Asian Indians, the median amount of barriers to seeking mental health identified fell around two barriers (Min = 0, Max = 7, IQR = 2.00) (Figure 1). There was a weak positive correlation between generational status and number of barriers identified to mental health care, r = .160, n = 70, that did not have a statistical significance (p = 0.168) (Table S2). Therefore, the hypothesis that first-generation Asian Indians would identify more barriers to seeking mental healthcare compared to second and later-generation Asian Indians was not statistically supported. Instead, it was observed that second and later-generation Asian Indians reported decreased access and more barriers to seeking mental health care than first generation Asian Indians. However, this observation was not strong enough to be statistically supported.

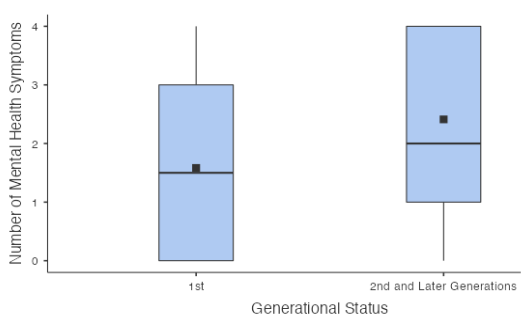

To test the second hypothesis and to determine the mental health symptoms of participants, I had respondents choose any or multiple of the following choices: 1) “Withdrawn from Friends and Social Activities,” 2) “Fear, Worry, or Anxiety,” 3) “Feeling Sad, Down, or Hopeless,” 4) “Mood Changes,” (Table S1). Participants could also select if they had none of the following feelings as well (Table S1). The median rate of mental health symptoms for first-generation Asian Indians fell at two symptoms (Min = 1, Max = 4, IQR = 1.00) (Figure 2). Similarly, the median value for second and later-generations Asian Indians identified was one mental health symptom (Min = 1, Max = 4, IQR = 3.00) (Figure 2). I also found a weak positive correlation between generational status and the number of mental health symptoms, r = .286, n = 70, and it had fairly strong significance (p = .016) (Table S2). Therefore, this hypothesis regarding second and later-generation Asian Indians identifying more mental health symptoms was statistically supported through this positive correlation.

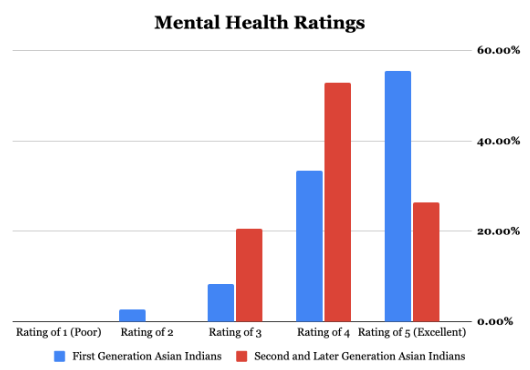

To test my third hypothesis, I had all respondents rate their mental health quality on a scale from 1-5, with one being poor and five being excellent. The majority of first-generation Asian Indians reported their mental health ratings as a five or excellent mental health quality, whereas ⅓ of first generation Asian Indians responded with a four as their mental health rating (Figure 3). On the other hand, the majority of second and later-generation Asian Indians reported a slightly worse mental health quality at a rating of four than first generation Asian Indians did (Figure 3). Only around ¼ of second and later-generation Asian Indians rated their mental health quality as excellent, compared to the majority of first generation Asian Indians, who reported their mental health quality as five (Figure 3). In addition, there was a negative correlation between generational status and mental health ratings, as second and later-generation Asian Indians were more likely to report lower mental health ratings than first generation Asian Indians, r = -.240, n = 70, that was found to be significant (p = .045) (Table S2). Therefore, this hypothesis regarding the majority of second and later-generation Asian Indians reporting lower mental health ratings was statistically supported.

To test the final hypothesis, I attempted to see if generational status played a role in discouragement or success in seeking mental health treatment. There were findings of a statistically significant relationship between generational status, as second and later-generation Asian Indians on average were more likely to be discouraged when seeking out mental healthcare compared to first-generation Asian Indians, X² (1, n = 70) = 4.36, p = .037. On the other hand, there was no statistically significant relationship found between generational status and success in seeking mental healthcare, X² (2, n = 70) = .866, p = .648. Overall, there was a significant relationship to reject the first part of the second hypothesis that first-generation Asian Indians would be more discouraged in seeking mental health care. Moreover, there was not a significant statistical association to support the second part of the final hypothesis.

DISCUSSION.

Overall, the majority of second and later-generation Asian Indians identified a higher number of barriers, a higher number of symptoms, reported lower mental health ratings, and reported being more discouraged from seeking out mental healthcare. These findings do reject my first hypothesis that first generation Asian Indians were more likely to identify more barriers to mental health care. However, they do support my second and third hypotheses, that second and later-generation Asian Indians were more likely to report having a higher number of mental health symptoms and lower mental health ratings than first generation Asian Indians were supported. Lastly, these findings reject the first half of the fourth hypothesis that first-generation Asian Indians would be more likely to be discouraged to seeking mental health care than second Asian Indians, and they do not support the second part of my hypothesis that second and later-generation Asian Indians would have less success to seeking mental health care than first generation Asian Indians. These results support the findings of previous research on barriers to mental health care [9]. Furthermore, these findings also support the conclusions derived from prior research in terms of identifying poorer mental health quality in second-generation Asian Indians (prior research hasn’t researched much into immigrant generations later than 2nd generation Asian Indians) [10, 12].

Limitations.

There are some limitations to this study that may have influenced the results. The study presents potential risks from sampling and respondent bias. The proportion of people from each gender and age was different, indicating some type of sampling bias. For example, as 36 participants (37.1%) identified as male, and 44 participants identified as female (62.9%), it may have skewed results in a certain light. Moreover, by only having a total of 70 participants, there might have been a sampling bias as the sample size may not have represented the full spectrum of first and second and later-generation Asian Indians in the U.S. In addition, 38.6% of all participants were from the ages 40-49, whereas the next biggest category out of the 6 was 50-59 (21.4%) (Table 1).

| Table 1: Demographic distribution of participants. | ||

| Gender | Age | Generational Status |

| Male (37.1%) | 5-17 (15.7%) | First Generation (51.4 %) |

| Female (62.9%) | 18-29 (12.9%) | Second and Later Generations (48.6%) |

| Other (0.0%) | 30-39 (4.3%) | |

| 40-49 (38.6%) | ||

| 50-64 (21.4%) | ||

| 65+ (7.1%) | ||

Overall, the limitations presented might have shifted or influenced the overall shape of the responses. Additionally, 26 participants (37.1%) were born in the U.S., 15 participants (21.4 %) emigrated to the U.S. at the age of 10 or younger, 7 participants (10.0 %) emigrated when they were 11-16, and 17 participants (24.3 %) emigrated from ages 17-29. This high concentration of participants emigrating to the U.S. before age 29 might have largely influenced the overall shape of the data because they emigrated early enough to possibly share the characteristics of both first, and second and later-generation of Asian Indians through the generation “1.5” phenomenon, indicating some sort of respondent bias. Complementing this is that 35 participants (50.0%) have lived in the U.S. for 30 years and above, so this might have largely influenced the responses because they might have already been accustomed to mental health services in the U.S. Another limitation may be that 6 participants (8.5 %) did not identify as citizens of the U.S., so these responses may have been influenced by a possible lack of access to mental health services or lack of acclimation to these services, indicating a type of respondent bias. A limitation of this study is that this survey did not collect open-response questions, which in further analysis could potentially give more in-depth insight on perceptions of barriers to mental health care in Asian Indians.

Future Studies/Implications.

Future studies on this topic should try to get a larger sample size in order to get more accurate/insightful results, use a uniform way of collecting responses, such as using the Likert scale for all questions, and should collect additional qualitative data (through an advanced mixed-method study) so more advanced statistical analysis can be conducted to yield new insights. Adding on to this, an equal number of individuals should be ensured for each gender and age, and should account for the generation “1.5” phenomenon. Other studies can research more in-depth about why second-generation and later-generation Asian Indians have poorer mental health ratings, a higher number of identified barriers, and higher numbers of mental health ratings; trying to find a root cause or origin of this trend.

As time progresses, studies can also compare the specific differences in barriers to seeking mental healthcare between second-generation Asian Indians and third and fourth-generation Asian Indians. Studies in the future can also focus more on the high cost of seeking out mental healthcare, additional barriers to seeking mental healthcare that wasn’t tested, and success rates (being able to find support from stable counseling services, medications etc.) in seeking out mental healthcare. Finally, studies in the future should be aware of the stigma within the population and should attempt to design studies that try their best to capture the true feelings of the Asian Indian community using unique methods.

CONCLUSION.

All in all, after data analysis was conducted on the survey results, it was found that the majority of second and later-generation Asian Indians had lower mental health ratings, higher numbers of barriers in seeking mental healthcare, and higher numbers of mental health symptoms, as well as feeling more discouraged in seeking mental healthcare compared to first-generation Asian Indians. Despite not evaluating the cause and origin of these barriers to seeking mental healthcare or certain mental health states of these Asian Indian individuals, this study is beneficial. Specifically, there are limited studies regarding the impact of generational status on mental health and access to mental health care in the U.S. Asian Indian population. I aspire to motivate many researchers to further investigate the mental well-being of both first, and second and later-generation Asian Indians, but to particularly focus on why second and later-generations of Asian Indians have lower access to mental health care and poor quality of mental health care.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS.

I would like to acknowledge my amazing research mentors, Dr. Tatiana Bustos and Mr. Brad Boelman, who have guided me throughout the entire research process and have helped shape this study to where it is today.

SUPPORTING INFORMATION.

Additional supporting information includes:

Table S1 – Frequencies of Identified Barriers to Seeking Mental Health Care and Mental Health Symptoms for the 70 Participants.

Table S2 – Correlational Matrix Tests conducted on the Variables Included in the Report.

REFERENCES.

- About Mental Health. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2023). Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/mentalhealth/learn/index.htm. (Accessed: 21st May 2023).

- Borenstein, Stigma, Prejudice and Discrimination Against People with Mental Illness. American Psychiatric Association (2020). Available at: https://www.psychiatry.org/patients-families/stigma-and-discrimination. (Accessed: 21st May 2023).

- Gopalkrishnan, Cultural diversity and mental health: Considerations for policy and practice. Frontiers 6 (2018).

- S. Derr, Mental Health Service use among immigrants in the United States: A systematic review. Psychiatric Services 67(3), 265-274 (2015).

- G. Yang, C. R. Rodgers, E. Lee, B. L. Cook, Disparities in Mental healthcare Utilization and Perceived Need Among Asian Americans: 2012–2016. Psychiatric Services 71(1), 21-27 (2019).

- Gautam, N. Jain, Indian culture and psychiatry. Indian Journal of Psychiatry 52(1), S309–S313 (2010).

- Z. Siddiqui, U. Sambamoorthi, Psychological Distress Among Asian Indians and Non-Hispanic Whites in the United States. Health Equity 6(1), 516–526 (2022).

- About the Foreign-Born Population. S. Census Bureau (2021). Available at: https://www.census.gov/topics/population/foreign-born/about.html. (Accessed: 16th May 2023).

- Muhorakeye, E. Biracyaza, Exploring Barriers to Mental Health Services Utilization at Kabutare District Hospital of Rwanda: Perspectives From Patients. Front. Psychol. 12 (2021).

- G. S. Khera, N. Nakamura, Substance use, gender, and generation status among Asian Indians in the United States. Journal of Ethnicity in Substance Abuse 17(3), 291–302 (2018).

- S. Panjwani, S. B. Manyam, P. R. Prasath, The Impact of Immigration Status on the Quality of Life Among Asian Indians in the United States of America. Journal of Asia Pacific Counseling 11(2), 109–124 (2021).

- P. Vaghela, K., Ueno, (2017). Racial-ethnic Identity Pairings and Mental Health of Second-generation Asian Adolescents. Sociological Perspectives 60(4), 834–852 (2017).

Posted by buchanle on Tuesday, April 30, 2024 in May 2024.

Tags: Asian Indians, Generational Status, Mental health care, Mental health quality