Data-Driven and Interview-Based Assessment of The Effects of COVID-19 on Domestic Violence (DV) Incidents in Nashville, TN

ABSTRACT

Women have long been vulnerable to domestic violence (DV). This study aims to determine whether DV cases increased from 2019 to 2020 in correspondence to the COVID-19 pandemic. Containing information on rape, homicide, and aggravated assault (RHA), pre-COVID-19 and post-COVID-19 databases were obtained from the Metropolitan Nashville Police Department (MNPD). A 6.9% increase occurred from 2019 to 2020 in RHA. Second, this study aims to identify consistent themes in two DV professional careers: Project Safe, the center for sexual misconduct at Vanderbilt University, and the DV division of MNPD. Interviews were conducted with PS and MNPD staff and were analyzed on the basis of the following 8 categories: most rewarding aspect of profession, most motivating case, responses, childhood DV, COVID, COVID rating, separation equals safety, and general advice. For PS staff, COVID-19 significantly impacted job responsibilities (p=0.014) and they stated a single motivating case influenced their career choice (p=0.014), where MNPD did not share these perspectives. All MNPD staff stated they had a listening and asking approach when responding to survivor’s stories (p=0.14), whereas PS staff had more diverse responses. MNPD all reported positive attitudes towards the separation equals safety approach (0.049).

INTRODUCTION.

Domestic violence against women is a prominent social and health issue. It is reported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) that every 1 in 4 women will experience intimate partner violence (IPV) at some point throughout their lifetimes [1]. However, not every incident is reported and the United States Bureau of Justice found that from 2006-2015, nearly 600,000 cases were unreported. Thirty-two percent were unreported due to the “personal nature” of the situation, 21% of the cases wanted to protect the offender, 20% felt the crime was unimportant or minor, and 19% feared retaliation from their offender and possibly from others [2]. Regardless of an unreported or reported case, women have reported that episodes of domestic violence leave long term physical and/or mental health scars, including depression, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress disorder [3]. Even help-seeking women have reported feeling depressed, and 58% of them reported being depressed upon leaving a safe shelter within 10 weeks [4].

Over the years, DV and the manifestation of feminism in general received conflicting public attention and opinions. In fact, “wife beating” was only considered illegal in the year 1920 [5]. In 2020, the issue of domestic violence only got more risky as the ongoing global pandemic of COVID-19 forced nearly everyone to quarantine. This puts women and children at a higher vulnerability against domestic violence [6]. This study aims to answer two objectives. The first to identify an increase in DV cases in the Davidson county and Nashville community, as a potential effect of the pandemic. Second, to identify persistent themes among two expert vocations dealing with DV: the Domestic Violence Task Force at Metropolitan Nashville Police Department (MNPD) and Project Safe (PS), center for sexual misconduct and its prevention at Vanderbilt University. It was first hypothesized that COVID-19 would likely increase DV incidents in Nashville, due to increased quarantine time. By mid June, Davidson county had reported 6,290 COVID cases [6]. It is also hypothesized that participants from the same profession are likely to share similar opinions since it’s predicted that values aligned with the individual and their profession is a factor for career choice [7].

MATERIALS AND METHODS.

Table 1. The list of questions used when interviewing PS and MNPD staff.

This study’s protocols were first reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board for the School for Science and Math at Vanderbilt, consisting of qualitative data comparisons and interview-based assessment. All participants provided written informed consent prior to data collection. Data comparison reports were obtained from the MNPD, and 2019 pre-COVID and 2020 post-COVID DV incidents in rape, homicide, and aggravated assault (RHA) were analyzed. Then, virtual interviews occurred via Zoom with enabled captioning, in partnership with (PS) and (MNPD). All calls were recorded to save a transcript file (no video files were saved), and participants had the choice to disable cameras, profile pictures, and any form of identification. The average call time was 43.16 minutes (12-100 minutes).

The same list of questions was used to facilitate both interviews with the PS and MNPD staff. Refer to Table 1 for the list of questions. During the preliminary stage of developing the questions, a portion of them has been developed using the training file from the New Jersey Division of Criminal Justice [8]. After conducting a total of six interviews, three with PS and three with MNPD staff members from different job positions (directory to specialty departments), eight themes were identified and decoded. The process of decoding the interviews started with a review of the transcript files that identified the questions with the longest and rigorous answers. The average time for the longest PS response is 4.53 minutes (0.09-13.1), and the average time for the longest MNPD response is 2.45 minutes (0.18-5.11). Then, each long question was used to identify the most similar responses among each group. This was concluded with 8 questions, which were used to develop the following 8 themes: most rewarding aspect=helping, most motivating case=yes, responses=listening and asking approach, childhood DV=yes, COVID= job responsibilities changed, COVID rating=high change, separation equals safety=positive attitudes, and general advice included seeking responses.

RESULTS.

It was hypothesized that DV cases in Nashville increased from 2019 to 2020, in correspondence to COVID-19. Quantitative measures were taken to test this, which consisted of analyzing the percent increase in all MNPD DV cases in RHA from 2019 to 2020. Additionally, it was hypothesized that participants within the same career group (PS or MNPD) will most likely share similar responses and vice versa, due to one’s familiarity and association with their colleagues. This was conducted using the Pearson chi-square test the statistical relationship between each category and career group.

MNPD Quantitative.

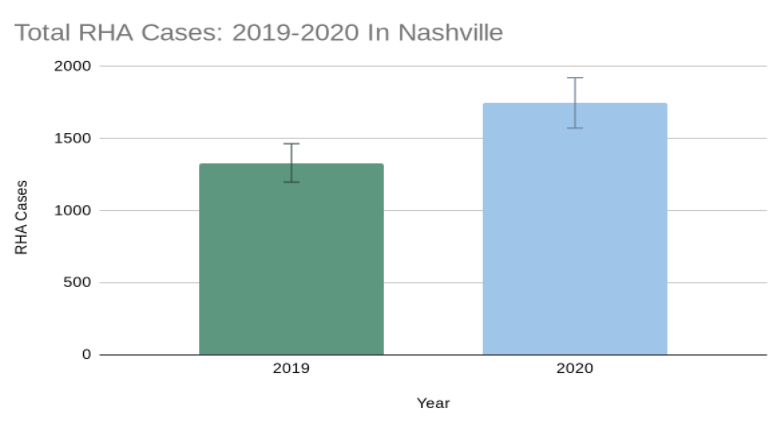

Obtained MNPD comparison reports from 2019 pre-COVID to 2020 post-COVID have shown a 6.9% increase from 1332 (2019) cases to 1424 (2020) cases in RHA (Figure 1).

Figure 1. The rape, homicide, and aggravated assault count (RHA) from 2019 to 2020 in the Nashville-Davidson County community, as reported by the MNPD.

Interview Qualitative.

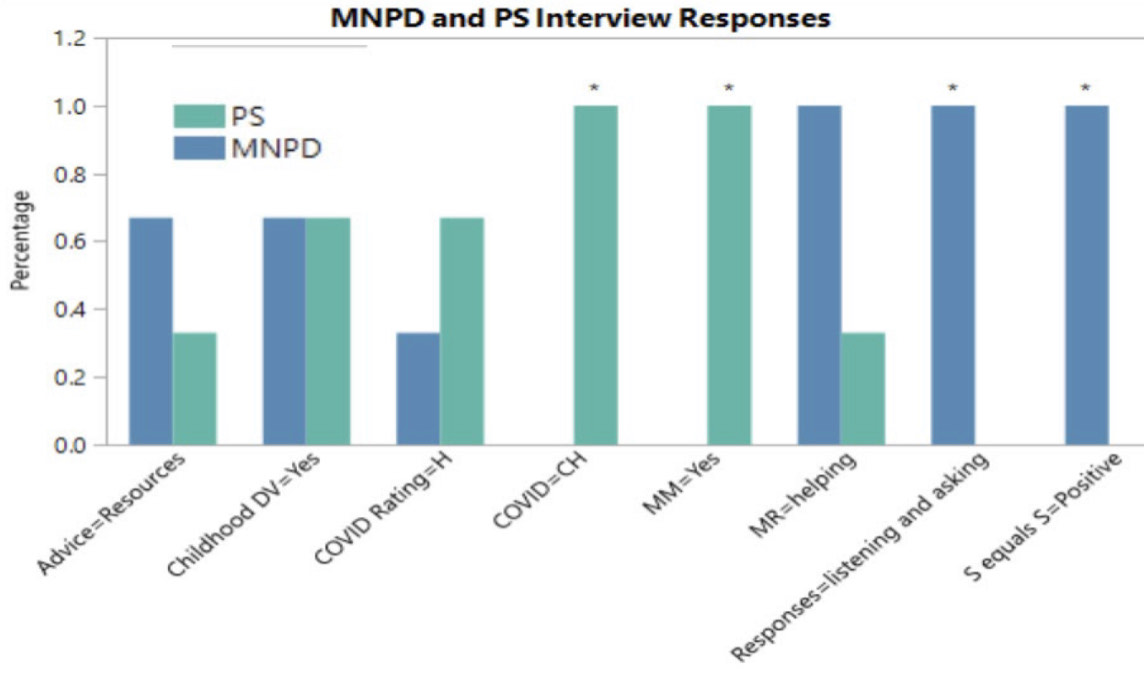

Each theme has its own scale because no standardized scale matched every single code. Then, all themes were inputted into JMP to identify the Pearson chi-squared value [9]. It was found that COVID-19 significantly impacted job responsibilities for PS when asked to rate the COVD-19 change on a 0-10 scale (0:minimal change, 10:high volume of change) (p=.014), and they claimed the presence of one specific DV case that stands out or constantly serves as a motivating factor for their career (p=0.14). On the other hand, MNPD did not report that COVID-19 negatively affected their ability to perform their job duties and did not cite a singular motivating case for their DV career. MNPD staff agreed that they use the listening and asking approaches when responding to survivors’ stories (p=0.14) and allude positive attitudes towards the separation equals safety procedure (p=0.049) (Figure 2).

Figure 2. The collected informational interview responses in all 8 themes and found a significant relationship between PS and job responsibilities’ effect from COVID, PS and a motivating case, MNPD and the listening and asking approach, and between MNPD and their positive support for separation equals safety.

DISCUSSION.

The purpose of this study was to understand the relationship between COVID-19 and DV cases in the Davidson-Nashville area pre and post the pandemic. It was hypothesized that there would be an increase in DV cases because by mid-June, Davidson County had reported 6,290 COVID cases, emphasizing more quarantine time [10]. Second, it was hypothesized that participants in the same profession (either PS or MNPD) will most likely have similar responses among their colleagues, and different responses among the opposite group. This has been developed by the concept of interprofessional collaboration (IC), which more commonly refers to colleagues with different professional backgrounds working together to achieve a common goal [7]. However, IC could also be used among similar backgrounds, especially when it’s involved with professional training of a new and inexperienced colleague.

The MNPD data shared reports on DV incidence in different areas, but the study focused precisely on rape, homicide, and aggravated assault (RHA), and found a 6.9% increase altogether, supporting the original hypothesis and highlighting the severity of the pandemic on DV. The increase in home time with the abuser proposes several ideas. The more a woman stays with her abuser falls within one or more of these reasons: lack of resources if she left, fear of detachment and emotional distress (particularly in long-term and prolonged DV relationships), culture and religious reputations, and self-sabotage.

The results of the interview analysis indicated that the PS staff experienced a significant negative impact on their job responsibilities as a result of COVID-19 and that they reported a single DV case that serves as a motivating factor for their career choice and development. Whereas, the MNPD staff reported that they did not experience an impact on their job responsibilities due to COVID because they’re essential workers, which is adequately supported by their low average for the COVID rating. They stated that the only major difference in their job responsibilities as a result of COVID-19 that occurred was going to apartment complexes and residential homes of DV victims to provide sources such as sanitary products and sometimes even food. Additionally, all MNPD participants agreed that they do not recall a particular case serving as a motivating factor for their career. This was fairly unique in a way since the participants come from three different job positions: captain of the division, sergeant and a detective, and still agreed by answering no. However, it’s crucial to mention that they answered “no” because they had different reasons that served as the motivator for their career choice, such as a college class that sparked their interest. Also, the MNPD is a larger cooperation and by the nature of the job, they serve a larger DV group (annual average of about 25,000 cases), whereas, the PS is on a college campus and has a more circumscribed population. With more cases, the professional and personal time with the victim could decrease. The MNPD claim that overall “the number of cases [they] get serves as the motivator” and that they “don’t try to live the cases” to prevent its effects on their personal lives and overall, their mental health.

For the MNPD staff, the results indicated that they all have a listening and asking approach when responding to survivors’ stories, whereas the PS staff had more diverse answers, including creating personalized safety plans and seeking the best options for each individual case. This is reasonably supported by the number of DV cases each group gets because when one-on-one time with the victim is emphasized more in a social advocacy and small organization than in a police department setting, individualized approaches would be the common answer. Additionally, the police are trained in a specific law-and-order way to respond quickly and effectively to DV incidents. The MNPD staff also reported positive attitudes to the separation equals safety approach, a procedure that essentially removes the victim from her offender for temporary or permanent safety. They claim that “it’s the best thing” and that the no-separation time is “the most dangerous time”, indicating extreme positive support for the approach. Whereas, the PS claim neutral-negative attitudes mainly because of the extreme “equal”. They agree that separation is not necessarily the “vaccine against domestic violence”, but rather it depends on each case, emphasizing the personalized approaches when meeting with victims one-on-one [11].

This study encountered several limitations, but mainly the limited small sample size of only 6 participants affected the study from furthering its initial goals to apply the findings and gained knowledge to a larger audience. A larger sample size would further enhance the generalizability of the study’s results, and could allow for more in-depth analysis on the effect of rank, age, experience, gender, and different professional backgrounds on their overall DV perspectives. Second, a missing perspective that if present, would yield a more niche specific to this project, is the survivors’ own perspective on the same themes. In the future, this study could focus on resolving its limitations and conduct a more specific study on a particular profession (either advocates or law enforcement) and focus on 1-2 of the mentioned variables above.

All in all, domestic violence has been a prolonged issue, but with this small study’s analysis, a new understanding on the resources used to help reduce the issue by investigating their personal perspectives could aid in specific protocols and legislation to stop the expansion and increase the reduction of the issue.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS.

I would like to thank my mentor, Dr. Menton Deweese, for her support and guidance throughout the entirety of the project. As well as, the partnership with Captain Rickey Bearden at the Domestic Violence Task Force Division of the Metropolitan Nashville Police Department (MNPD) and the director of Project Safe (PS), Ms. Cara Tuttle-Bell. Both of these individuals have been really helpful and the study depended on their partnerships. I would also like to thank the School for Science and Math at Vanderbilt (SSMV) and Metropolitan Nashville Public Schools (MNPS) for their joint program to make this study possible, and my mom for her unconditional love.

REFERENCES.

- R. Hueker , K. C. King, G. H. Jordan, W. Smock , in Domestic Violence (StatPearls , Treasure Island , Florida , 2021).

- A. Reaves , Police response to domestic violence, 2006-2015. U.S. Department of Justice,Office of Justice Programs, Bureau of Justice Statistics (available at https://bjs.ojp.gov/content/pub/pdf/prdv0615.pdf).

- E. Stewart, G. E. Robinson, A review of domestic violence and women’s mental health. Archives of Women’s Mental Health. 1, 83–89 (1998).

- Campbell, C. M. Sullivan, W. S. Davidson, Women who use domestic violence shelters: Changes in depression over time. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 19, 237–255 (1995),

- Ramsey , C. B. Domestic violence and state intervention in the American West and Australia, 1860-1930, Available at: https://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1030&context=ilj. (Accessed: 3rd December 2021)

- Bradbury-Jones, L. Isham, The pandemic paradox: The consequences of covid‐19 on domestic violence. Wiley Online Library (2020).

- Green, B. N. & Johnson, C. D. Interprofessional collaboration in research, education, and clinical practice: Working together for a better future. Journal of Chiropractic Education 29, 1–10 (2015).

- Interviewing techniques in domestic violence cases (available at https://www.nj.gov/oag/dcj/njpdresources/dom-violence/module-four-student.pdf).

- JMP®, Version 14 Student Edition. SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, 1989–2021.

- Timms, Coronavirus in Tennessee: Timeline of cases, closures and changes as COVID-19 moves in. The Tennessean (2020) (available at https://www.tennessean.com/story/news/health/2020/03/26/coronavirus-tennessee-timeline-cases-closures-and-changes/2863082001/).

- James-Hanman, S. Holt, Post-separation contact and domestic violence: Our 7-point plan for safe[r] contact for children. Journal of Family Violence. 36, 991–1001 (2021).

Posted by John Lee on Saturday, May 7, 2022 in May 2022.

Tags: Advocates, COVID-19, Domestic Violence (DV), Intimate Partner Violence (IPV), Law Enforcement