Review by Alicia Marie Brandewie

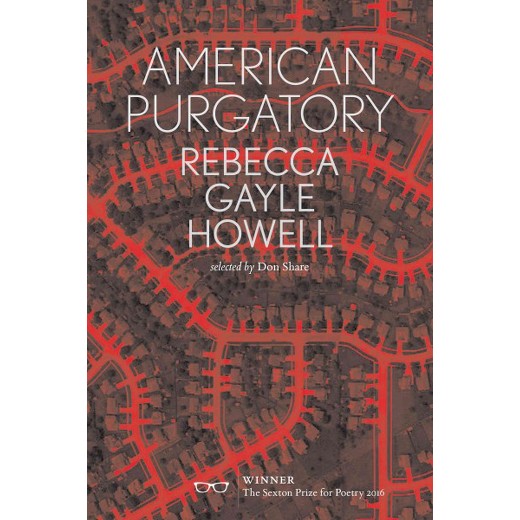

Rebecca Gayle Howell’s American Purgatory (Eyewear Publishing, 2017), winner of The Sexton Prize for Poetry 2016 as selected by Don Share, editor of Poetry magazine, is an air-raid siren warning against an impending dystopian future where capitalism, the government, climate-change, and faith have all gone feral. A future when “water is a ghost”—physically gone but still exacting supernatural powers over the thirsting population. The collection begins by (re)building our world from the first poem’s title: “It’s Like This.” “We are the ones keeping it going. And under us, others keep us going,” the never-named female narrator tells us. The hierarchy in this society is clear, insurmountable, and stacked in the favor of corporations and a powerful government.

Howell offers a brutal vision of our possible future through the dust-itched but observant eyes of the poems’ narrator. Neither hero nor antihero, her resistance to this putrid society comes not in the blazing of guns, which she has ready access to, but in her candor and self awareness: “I’d blame/ the Brutes, but I know it’s my own dread I smell / fetid and kicking.” The collection revolves around a cast of characters baptized by dust and desecration: the laboring narrator; Brother Slade, juxtaposed as both “a Bible man” and “Praise! the Devil”; Little, who despite his missing hand is a step above the others with enough capital to draw water; and The Kid, a Brute, the lowest caste of citizens born with severe deformities from rampant, unregulated chemicals in commercial farming. Howell conjures a doppelgänger society of distant hyper-wealth for a few while creating desperate poverty — wanting cash, wanting God, wanting love, wanting safety — for the many. Here is a society that knows to “Give up what you need for want. Don’t ask / the interest rate.”

After opening the world to us in a two-page prose poem, the book narrows into exacting precision, staking out the boundaries of nearly-our-world through visual poems and limiting the remaining text poems to roughly sonnet-sized single stanzas form. The visual poems, or poem maps, are both arresting and functional: they force the reader to question their understanding of what is and is not considered a poetic text by contributing necessary information to the narrative through non-literary means. The visual poems hearken back to the etching style of the past. They are sourced from colonial-era images set within the expansive emptiness of the future depicted via white space, and highlighted with a few choice words. They form a sub-sequence portraying the landscape of spirit. Take, for example, “Map #2: Detail of Town / (believe)” which adds a universal ambiguity to both the characters and the setting of the collection by juxtaposing a figure that is both /neither /all genders, races, and ages besides a pattern that could be /is all at once an aerial map, a closeup of tree bark, detail of water, and an animal hide. American Purgatory takes place all at once in both a very specific small, drought-choked town and the globalized world. Its warning is universal.

Howell brings us to bear witness to the precarious world and the four core characters as they endure cycles of destruction and desperation: physical, economical, spiritual, and emotional. In a world filled with pestilence and devoid of satisfactions, there is a blending of desires. The narrator and Slade find deep pleasure in shooting rabbits in a place where “killing feels so little like dying, praise him / who made it so.” Howell’s lyricism can be an uncomfortably large leap at first, but it is not an obscuring tactic, and the author clearly trusts her readers. Howell knows we are all scholars of the American late-capitalist experience, and feel the threads of evangelical religion, classical mythology, rearing, thirst, climate change, disability, gender, exploitation, and social-stratification. All readers will “see Golgotha repeating.”

American Purgatory is not without redemption or mercy. The narrator is forthright: “I offer grace.” To get there, she—and we—must travel beyond the artificial safety of the town, its system of exploration, beyond the fields and Brutes, into the wilderness. The narrator in her trial knows “you will not see the flag of warning / I’ve become, since no one gets out of here / alive, boys, not one.” If the narrator is able to resurrect her water on her own, there is hope yet for the rest of us, for a future when we can break the cycles of desperation, poverty, apathy, malice, and predation.