Professor uses centuries-old martial arts form to educate students about Brazilian democracy

On a hot, muggy August evening, a group of masked students followed Gilman Whiting, associate professor of African American and Diaspora Studies, onto the lawn in front of Wilson Hall. There, they took up socially distanced positions and began working their way through a series of exercises designed to encourage rhythm, flexibility, balance, and cooperation.

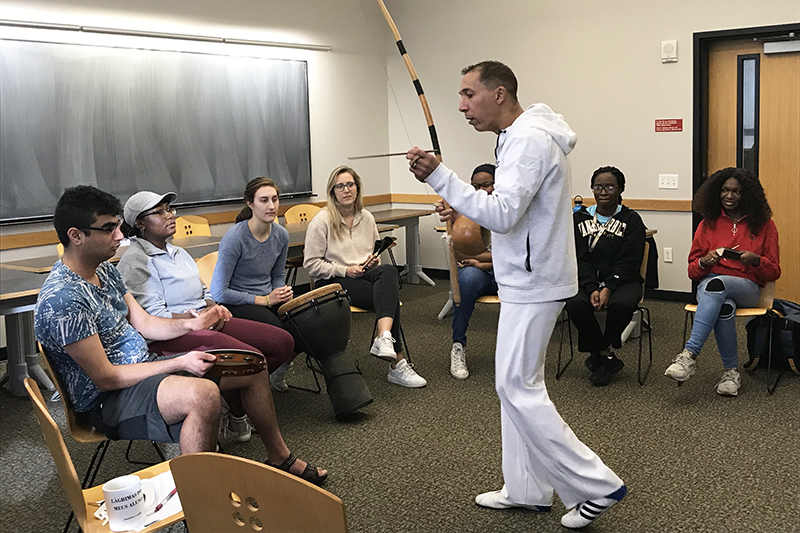

The exercises are part of Whiting’s Fall 2020 course Capoeira: Afro-Brazilian Race, Culture, and Expression. Meeting for three hours on Wednesday evenings, each class begins with a lecture and discussion inside Wilson Hall, then migrates to the lawn for capoeira practice. Capoeira is a martial-arts form created approximately 500 years ago by enslaved Afro-Brazilians. Whiting, who specializes in the sociology of race and sports, is using the activity as a lens through which to teach students about slavery and democracy in Brazil.

“I want our students to understand the international impact of the African diaspora. There’s no country in the world that has more descendants of formerly enslaved Africans than Brazil,” he said.

Outlawed following the abolition of Brazilian slavery in the 1880s, capoeira survived as an underground art form until Brazil’s government relaxed restrictions on it in the 1920s and 1930s. UNESCO granted the activity special protected status as intangible cultural heritage in 2014.

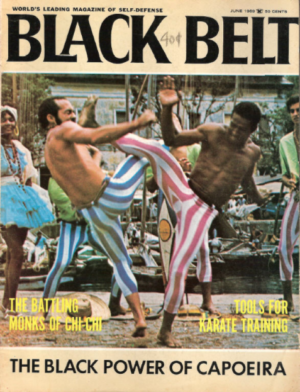

Whiting, who is a tenth-degree grand master of Kempo karate and holds several black belts, became interested in capoeira after seeing it in the 40th-anniversary issue (2001) of Black Belt Magazine. The issue featured a 1969 cover photo, captioned “The Black Power of Capoeira,” showing two men in full action kick. “I had been involved in martial arts for more than 20 years and never knew about any art form with African diasporic roots,” Whiting said. “I needed to see this for myself.”

After traveling to Brazil to meet capoeira legend Grão-Mestre (Grand Master) João Grande, Whiting established a capoeira club at Hamilton College, where he was then teaching. Whiting came to Vanderbilt in 2004 and, after working with a graduate student to establish a capoeira club, began traveling regularly to Brazil to learn more about the country’s language, culture, and history. He has since done several capoeira events and one-credit classes for Vanderbilt students. The popularity of those offerings, plus the potential for better exploring capoeira’s rich and complicated history, prompted him to create the current course.

Through the study of capoeira and its significance, Whiting wants his students to gain a better understanding of the magnitude and long-term impacts of the European slave system as it operated in Brazil. While the slave-trade route from Africa to the U.S. was a 3-4-month trip, the journey from Africa to Brazil took just 2-3 weeks. As a result, it was easier both to traffick in and to replace Brazilian slaves. Brazilian slave owners therefore tended to buy more slaves and to treat them more brutally than did their American counterparts. Ultimately, approximately 5 million enslaved Africans were forcibly transported to Brazil, compared to 400,000 transported to the U.S. In addition, the Portuguese government occupied Brazil itself for more than 300 years, harvesting large quantities of wood, rubber, and coffee for use in the “triangular trade” with the U.S. and Europe.

Whiting said that this history of colonization has created a power dynamic that favors whites in a nation where more than half the population is Black or Indigenous. Through his research, Whiting has found that postcolonial Brazilian leaders have employed a number of tactics to maintain white supremacy, including destroying official records in predominately Black regions and actively encouraging white Europeans to move to Brazil.

“I’m trying to paint a bigger picture of the historical backdrop so the students can understand how modern democratic rule has been set up,” Whiting said. “The Brazilian government says it’s democratic, but it’s really not. It’s controlled by the descendants of colonizers. Democracy has become about appeasing the masses or making the masses go along with the rules. I want my students to ask, ‘Does democracy even exist, or is it just the illusion of democracy that exists?’”

Whiting also wants his students to draw instructive comparisons between Brazil and the U.S. Both nations have strong regional divides when it comes to politics and race. Both are grappling with the legacy of police brutality against citizens of color. Both are major players in the world economy. And, perhaps most importantly, both have elected populist leaders on the heels of more liberal governments.

Given that most of his students come to Vanderbilt knowing nothing about Brazilian history or politics, Whiting’s most important goal is to inspire them to learn more: to sign up for a language or history class, travel to Brazil, or take more classes in his department. And that’s why he leads them out onto Wilson Lawn every week—because the practice of capoeira itself provides an object lesson in growth.

“I’ll have them bend from the waist to reach for their toes. Some of them will only get to their knees, or their shins, but I tell them, ‘The important thing is where you are today versus where you will be the last week of class. Will you get two inches further? Four inches further? Will you stay in the same place but do it every day?’,” he said. “That’s the same way we look at democracy. Learning in small, disciplined steps: where you are today versus where you are at the end of the semester.”