Teaching Beyond the Gender Binary in the University Classroom

| Print Version |

| Cite this guide: Harbin, B. (2016). Teaching beyond the gender binary in the university classroom. Updated by Roberts, L.M. et al., (2020). Vanderbilt Center for Teaching. Retrieved [today’s date] from: https://cft.vanderbilt.edu/guides-sub-pages/teaching-beyond-the-gender-binary-in-the-university-classroom/ |

by Brielle Harbin, CFT Senior Graduate Teaching Fellow, 2015-20161 Updated by Leah Marion Roberts, Graduate Teaching Fellow, 2019-2020, to reflect current language, understandings, and recommendations related to moving beyond the gender binary. Updates made in collaboration with Roberta Nelson and Chris Purcell of the Vanderbilt Office for LGBTQI Life and Brielle Harbin, Ph.D., Assistant Professor of Political Science at the United States Naval Academy2

|

Introduction

In recent years, students on campuses across the country have become increasingly vocal in resisting binary thinking with respect to gender identity and expression. In an editorial that appeared in the Chronicle of Higher Education, Schmalz (2015) interviewed a dozen Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer plus (LGBTQ+) students, many of whom identified as gender fluid, genderqueer, gender non-conforming, transgender, and/or non-binary, and found these students experience a great amount of anxiety and frustration. Several students expressed fear of instructors and staff misgendering them or committing other microaggressions. They described their anxiety about being “outed” by professors in their classes and being forced to “come out” every semester when they must talk with faculty about their names or pronouns. One student shared, “Every day it’s scary to just be in class, not knowing what people are going to say” (Schmalz 2015). Another student explained:

Increased awareness around the complexities of gender identity and expression has given rise to questions regarding best practices for promoting gender inclusivity on campuses across the country. From debates about the appropriate policy regarding student name changes to awareness campaigns about pronoun usage, university administrators, professors, and students collectively are struggling to find a more just and nuanced understanding.

Students have voiced experiencing anxiety, stress, or isolation when their pronouns or identities are not honored in a classroom. This guide is intended to reflect the University’s commitment to diversity, as outlined in the non-discrimination policy, and to provide best practices for respecting gender identity and expression in the classroom.

This video provides another perspective on the complexities of being non-binary in the United States.

Respecting gender identity and expression in the classroom affirms students who identify as non-binary, gender non-conforming, and/or transgender, and additionally creates a culture of inclusion and diversity in education that has indirect benefits to all. Research shows that making learning spaces accessible to non-majority students benefits all students by enhancing creativity and improving problem solving and decision-making (Levine and Stark 2015; Phillips 2014). Additionally, giving students the opportunity to self-identify the names and pronouns they use in the classroom benefits all students, including international students and students who use their middle name as their primary name.

This teaching guide focuses on teaching beyond the gender binary in the university classroom, and thus attends to the experiences of non-binary students. Many of the points in this teaching guide are also applicable to transgender students. Some transgender individuals identify as non-binary or gender non-conforming and some do not. Similarly, some non-binary or gender non-conforming individuals identify as transgender, and some do not. It is important to recognize that the experiences and identities of transgender and/or non-binary individuals may overlap but are not the same. To this end, throughout this guide, we focus on students with non-binary gender identities. We note that these experiences also may be relevant for transgender students in many cases. The end of this guide has links to several resources with glossaries of terms that may be beneficial to readers.

Further, this guide is focused specifically on non-binary students in university classrooms. Teachers, administrators, staff, and other non-student individuals on campus also may identify as non-binary and/or transgender and this guide does not speak to such experiences directly. It is important to note that these individuals are faced with unique puzzles, possibilities, challenges and opportunities in the classroom and elsewhere on college campuses.

Common Challenges to Gender-Inclusive Teaching and Some Evidence-Based Solutions

There are several common challenges to gender-inclusive teaching. While these challenges often manifest differently across disciplinary contexts, they all arise as obstacles to disrupting the long-standing misconceptions of gender as a binary construct. In the following subsections, we discuss twelve challenges that can arise when cultivating a gender-inclusive classroom environment. We interweave the discussion of the challenges with research-based practices meant to address the issues.

Fluency with Gender Non-Binary Vocabulary

Cultivating a gender-inclusive classroom environment requires a familiarity with an array of concepts related to gender identity and expression. Consequently, efforts to promote a gender-inclusive environment require both consciousness raising and learning opportunities for students and leaders in the classroom. In particular, there are several conceptual distinctions that are crucial to understand when working to construct a gender-inclusive classroom.

Sex assigned at birth versus gender identity

Individuals often conflate sex assigned at birth with gender identity. However, these terms are distinct. Sex is assigned at birth by a medical practitioner, and is largely determined by physical attributes such as external genitalia, sex chromosomes, sex hormones and internal reproductive structures. Sex assigned at birth is binary (male/female). Gender identity, on the other hand, is an individuals’ internal sense of their gender which may or may not match the sex that they were assigned at birth.

Gender identity versus gender expression

While gender identity and gender expression can be related, they do not have to be. Gender identity is individuals’ internal understanding of themselves as it relates to gender. Gender expression, on the other hand, is how individuals express their gender through clothing, demeanor, etc. How one expresses their gender is not necessarily related to their gender identity. Gender expression may be a way individuals play with external gender performance and explore roles, while gender identity is an interior sense of self. Both can be fluid and change over the course of one’s life, and they need not change together.

Sexual identity versus gender identity

Individuals often conflate sexual identity and gender identity. Sexual identity refers to individuals’ romantic and sexual attraction to others, or lack of attraction (asexual identity). Gender identity describes individuals’ internal understanding of themselves as it relates to gender. Sexual identity is a separate concept that refers to an individual’s sense of romantic and/or sexual attractions.

GLSEN, an organization that works to support and affirm LGBTQ+ youth, provides a useful infographic and discussion guide that provides additional information on gender and gender terminology.

The Office of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer, and Intersex Life has curated several resources about gender that might be useful to course instructors.

Familiarity With and/or Commitment to Gender Non-Binary Topics

Topics related to non-conforming gender identities

Some students and leaders in the classroom may have limited prior interactions with transgender and/or non-binary individuals. Consequently, instructors and students may be unfamiliar with the experiences of non-binary and/or transgender people. These experiences may include (but are not limited to): feeling anxiety when using public restrooms; feeling disrespected when others make assumptions about their gender, name, and pronouns; feeling unsafe in learning spaces on campus; and experiencing high levels of discrimination and harassment. Importantly, as previously noted, some leaders in the classroom personally identify as non-binary and/or transgender, and their experiences in the classroom are unique.

The following provide a more detailed explanation of transgender and/or non-binary individuals’ anxiety about using public restrooms, thoughts about the intent of those who misgender them, and perceptions of safety on college campuses.

Even those who already have a more extensive knowledge of topics related to gender inclusivity may not entirely understand the impact of gender identity and expression on non-binary individuals. For example, they might not understand how other dimensions of individuals’ social identity (i.e. socioeconomic, religious, race, etc.) converge with their gender identity, and affect how others perceive them.

Learning about non-binary identities

Students may exhibit considerable variation in their commitment to learning about non-binary gender identities. Variation in students’ commitment may be rooted in lack of familiarity with non-binary individuals, ideology, culture, or religious background, and may lead to discomfort when engaging course materials that include the voices and experiences of non-binary individuals. This discomfort may be rooted in fear, shame, disgust, frustration, confusion, etc.

Clark, Rand, and Vogt (2003) observe that students may sometimes hold onto their current understanding of gender roles “like lifelines in class discussion” when confronted with information that challenges their existing views (2003, 3). According to the authors, this occurs because these critiques may threaten students’ “sense of self” and, as a result, be perceived as an “attack” (Clark, Rand, Vogt 2003, 3).

Respecting the identities of non-binary individuals

Both students and instructors may exhibit varying levels of prior experience engaging with topics related to gender identity and expression. For those who lack experience, it may seem unclear how to ask others about their gender pronouns in a respectful manner or how to intervene when someone has been misgendered.

The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee’s website offers a guide about pronoun usage that can be found here.

Other gender affirming practices include:

- Only call roll or read the class roster aloud after providing students with an opportunity to share with you the name and pronouns that they use and those they want you to use in the class.

- Allow students to self-identify their name and pronouns. Remind students that they can indicate their pronouns on YES.

- Set a tone of respect the first day of class as part of the course expectations and connect this discussion with honoring one another’s names and pronouns. Model this by including your name and pronouns with the class on the first day.

- Acknowledge when you’ve made a mistake about someone’s pronoun and correct yourself.

- If a student shares their gender identity with you, do not disclose the student’s gender identity to others unless you have obtained their consent. Note that some students will be comfortable with some names and pronouns in particular spaces, and different names and pronouns in other spaces.

- When/if you have obtained such consent, honor students’ names and pronouns in all university settings including (but not limited to): office hours, classroom, student group meetings, or when speaking with other faculty or staff, unless the student indicates settings in which they would like you to use a different name or pronoun.

- Honoring students’ names and pronouns includes making sure that other people use the correct name and pronoun for that student. If someone else misgenders a student by using an incorrect name or pronoun, politely provide a correction whether the person who was misgendered is present or not.

Do not ask personal questions of transgender and/or non-binary people that you would not ask of others. Such questions include inquiries about the person’s body or body parts, medical care, former name, why or how they knew they were transgender and/or non-binary, their sexual orientation or practices, their family’s reaction to their gender identity, or any other questions that are irrelevant to the classroom context unless the student explicitly invites these questions or voluntarily offers this information.

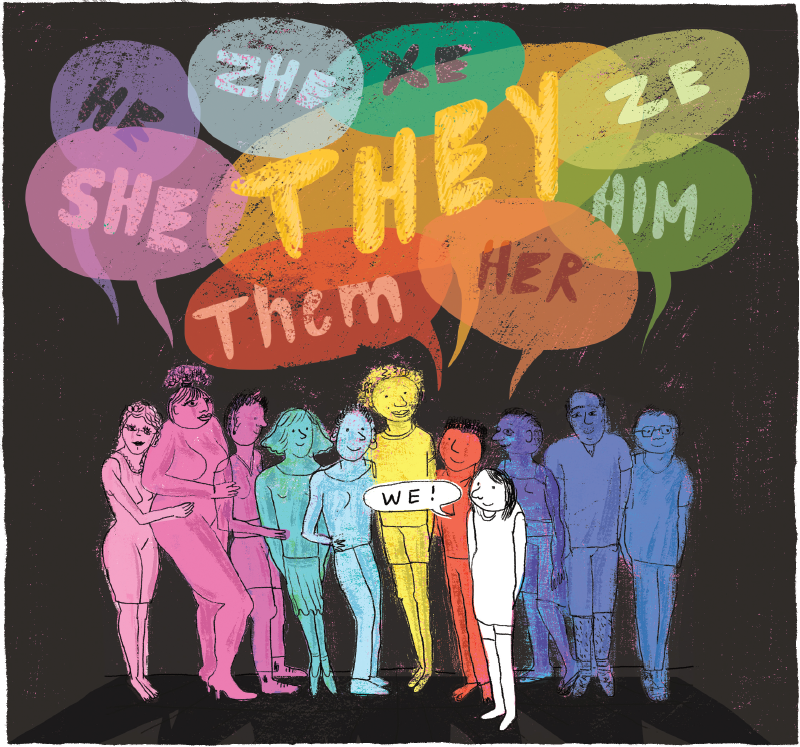

Implementing Gender-Inclusive Pedagogical Practices

The Gender Inclusivity Task Force at Vanderbilt recently developed a gender pronoun poster which provides information on gender pronoun usage and proactive ways for instructors to affirm Vanderbilt’s commitment to gender inclusion. This poster includes a set of terms that are common in the current context; however, students’ gender identities are personal and can be fluid. As such, this poster is meant to serve as a guide, not a definitive list of gender pronouns. The Vanderbilt English Language Center has produced a supplement to this pronoun guide that may be of special interest to international students, faculty, and staff.

These strategies include:

- Offering your name and pronouns when introducing yourself, even to familiar colleagues and students.

- Including your gender pronouns in your email signature and syllabus.

- Asking students their names and pronouns rather than making assumptions from the class roster or their gender presentation.

- Not using gender pronouns for people who have not explicitly told you what pronouns they use.

- Referring to students by the names and pronouns they identify with both inside and outside of the classroom (unless the student uses different names or pronouns in contexts outside the classroom).

- Substituting gender binary language for more inclusive language such as “everybody,” “folks” or “this person.”

- Respecting students’ privacy and only sharing their gender identities after receiving their consent.

- Apologizing when you make a mistake and misgender someone, and subsequently making deliberate efforts to not repeat your mistake (e.g., practice to yourself speaking about that person using their correct pronouns and name until it becomes familiar).

Collecting information about students’ gender pronouns

Inquiring about students’ gender pronouns may, at first, feel awkward for educators. This discomfort may be a result of feelings of uncertainty about how to ask students for this information. Uneasiness may also stem from uncertainty about how to maintain an atmosphere of mutual respect over the course of a semester.

Professors must decide individually how to best honor the names and pronouns from the students in their classroom. There are two common concerns that lead to confusion about asking a student to share their pronouns:

- First, is asking a student publicly for the name and pronouns that they use overly invasive?

- Second, does asking students to share their pronouns force them to repeatedly “come out?”

Instructors’ views on these questions likely shape their understanding about the most appropriate course of action.

There are a variety of approaches that can be adapted by instructors based on the discipline, class size, course topic, etc. In all of these options, the disclosure of name and pronouns is not mandatory, but there is a strong effort to make space for those who would like to share. These approaches include:

- Create a pre-class survey that provides a space to disclose this information using Survey Monkey, Google Forms, or a related polling platform. Include on the form space for students to give you details about their pronouns if they choose, such as pronouns/names they want used during office hours versus names/pronouns you use in the classroom context.

- Pass around a seating chart or sign-in sheet that ask students for their name and, if they choose, pronouns. Include a blank space for this information rather than a box to check with pre-specified options. The former approach allows students to express a wider range of pronouns. Consider explaining what pronouns are and modeling how to use them for students who are unfamiliar with what a pronoun is.

- Encourage or require students to meet with you in office hours to learn more about what will help them to learn and flourish in the class, which could entail discussion of many topics, including names and pronouns.

- Consider asking students if there are any contexts in which they would want you to use a different name or pronoun.

- Give all students the option to share their chosen name and pronouns. Do not only ask this information of students who you believe might be non-binary and/or transgender based on their gender presentations.

- Model the importance of not making assumptions about pronouns by introducing yourself with your pronouns, and inviting others to share if they would like to.

Once you have collected the names and pronouns that students use, it is important to honor these requests in all course-related classroom interactions. Doing so fosters a sense of mutual respect that is crucial in cultivating inclusive classrooms.

Here are several techniques for learning (and remembering) students’ names

Finally, when gathering information about students’ names and pronouns, it is imperative that course instructors not expect non-binary and/or transgender to “represent” the “non-binary and/or transgender perspective” in classroom discussions. Instead, consider including course materials that offer feedback from self-identified non-binary scholars to flesh out the multitude of perspectives on a given topic (Abbott 2009). The latter approach reduces the burden placed on non-binary students.

Maintaining a classroom environment that is fully respectful of students’ gender identity and expression over the course of the semester

Conflict may arise when creating (and trying to maintain) a gender-inclusive classroom environment. In these moments, instructors and teaching assistants may feel uncertain about how to appropriately intervene, particularly when a student has been misgendered or when microaggressions occur. Despite discomfort, it is the instructor and teaching assistants’ role as the leaders in the classroom to intervene. This is often the case even when these “teaching moments” are not directly related to the course content.

One of the best ways to maintain a positive classroom environment is be proactive about establishing norms of mutual respect from the first class meeting. For many instructors, it is customary to communicate expectations about course assignments and attendance on the first day; however, incorporating expectations about healthy communication, conflict and respecting one another’s gender identity tends to be less common. As a result, instructors may miss an important opportunity to cultivate a welcoming and gender-inclusive classroom atmosphere. More importantly, modeling such behavior may give students a better sense of how to conduct themselves and may build trust in the learning community of the classroom.

For additional ideas about establishing a welcoming and inclusive classroom environment,

check out the Vanderbilt Center for Teaching’s teaching guide titled “First Day of Class”.

For instructors who choose to express their expectations about communication, conflict and mutual respect, there are many ways this conversation might unfold. One possible approach is to begin the semester with a conversation about the importance of honoring one another by correctly pronouncing names, not assuming the gender or pronoun that people identify with, and consistently using the pronouns that people use once you have asked.

Another approach is to develop a document that outlines your expectations of mutual respect and present it to students during the first week of class. After presenting it to students, you might allow them to add to the document and use the final product as “group agreements” in your classroom. Or, the document may be developed with students from the start, particularly in courses where complex and challenging issues may be discussed on a regular basis.

This mutual respect document was developed in the Physics department at Ohio State University.

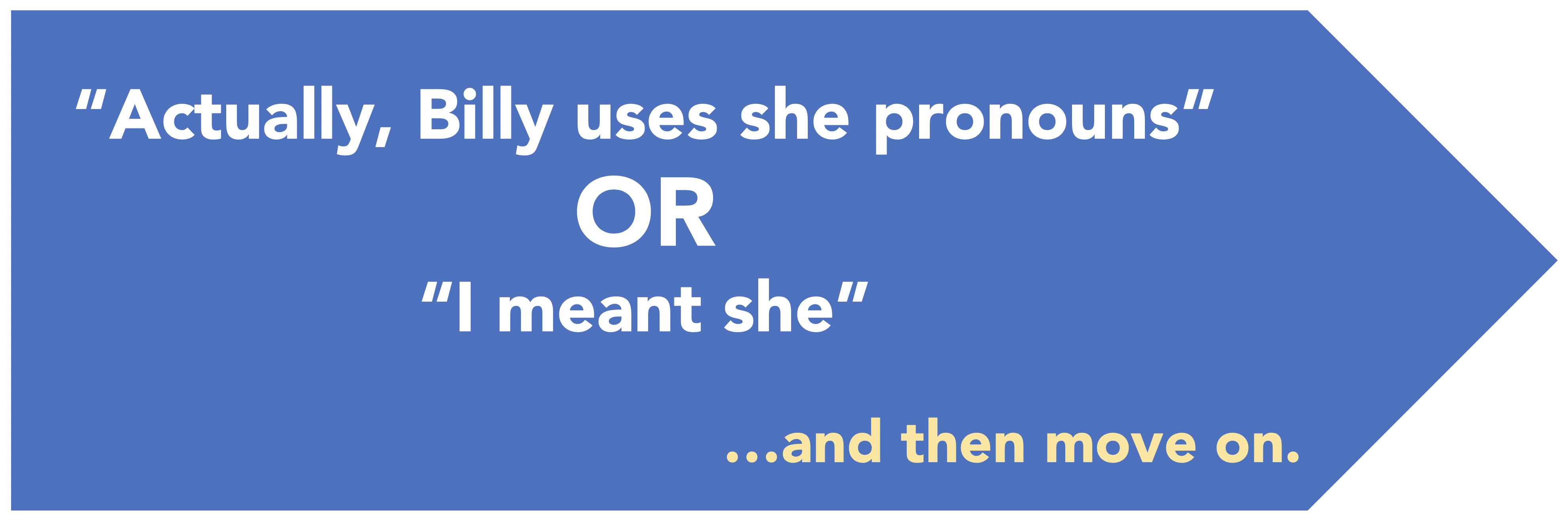

Beginning the course in this way provides an opening to talk about conflict before it arises. As part of this conversation, you might discuss how you will react and how you want others to react when someone (another student or you) misgenders a student. Some phrases might include:

Discussing this language outside of a “hot moment” allows students to learn about topics of gender identity and expression without activating defensive reactions. Moreover, it may head off potential conflict by having students engage in these important conversations before a breakdown of understanding occurs.

For further ideas on establishing a positive environment and providing a space for students to get to know one another in the classroom setting, check out these first day ice-breakers activity ideas.

When hot moments do arise, it is not advisable to avoid difficult or uncomfortable conversations. While it may feel awkward to stop and correct your (or a students’) pronoun usage, failing to act could be seen as a personal affront against transgender and/or non-binary individuals since it disrespects, excludes, or erases their identity.

Remember, students will naturally look to you for cues about the importance of gender-inclusivity owing to your role as a leader in the classroom. Be mindful of the verbal (and non-verbal) messages you send. If you are consistent in using the names and pronouns that students identify with, in most cases students will follow your lead and exert a similar level of effort in respecting their peers’ gender identity and expression. Faculty and staff may benefit from seeking out development and training opportunities that allow them to practice using these skills in order to become more comfortable with handling situations related to gender and pronouns as they arise in the classroom.

Incorporating non-binary voices into course materials appropriately

Course instructors may decide to include authors with non-binary gender identities into their syllabi with the intent of broadening the range of voices included in course materials. In doing so, however, instructors must be careful to avoid homogenizing, exoticizing, or tokenizing non-binary experiences.

AVOID #1:

Suggesting non-binary authors represent the beliefs of all non-binary individuals or using non-binary students as specialists.

Students who are unfamiliar with gender identity topics, or have limited experiences interacting with non-binary individuals, may be especially tempted to project the ideas of these authors onto all non-binary people. Similarly, it might seem like asking a student to speak about a community they are a part of would be a good way of getting the student involved. However, doing this creates a situation where you could be outing the student, asking them share something they do not have totally figured out yet, or setting them up to give one representation of the LGBTQIA+ community that then seems like a monolith to other students. If you are planning on directly discussing an identity that one of your LGBTQIA+ students holds, it would be best to have a private conversation with them prior to the class discussion so they are prepared and have the opportunity to decide if they will contribute in class.

AVOID #2:

Allowing students to inappropriately probe into the lives of non-binary individuals.

This act risks some exoticization of these individuals as Other or object, and therefore potential exploitation. Inappropriate remarks may center on salacious details or seek to gain some kind of entertainment or pleasure value from the experiences, identities, etc of non-binary individuals. Students tend to pursue this line of questioning when the learning objective for a reading or assignment is not made explicit, or when the instructor has not set up appropriate expectations and boundaries.

AVOID #3:

Embracing one token voice or a narrow set of non-binary voices into classroom readings.

Instructors may unintentionally include a narrow set of non-binary voices into their courses, which reinforce other forms of social power. It is important to include a diversity of gender non-binary backgrounds. For example, non-binary individuals exhibit a wide array of racial/ethnic, socio-economic, educational, etc. backgrounds. Given this diversity, it is important to avoid privileging some voices/backgrounds over others when incorporating non-binary voices into your syllabi.

AVOID #4:

Focusing on “coming out” stories when incorporating non-binary voices.

Instructors may include non-binary course materials that center on the experience of “coming out” as non-binary in an effort to provide an accessible starting point in gender identity classroom discussions. This practice is often harmful because it trains students’ attention to anecdotal experiences rather than interrogating broader systems of power (Courvant 2011, 30). Consequently, students miss the opportunity to explore the ideological dimensions of gender and sexuality and how broader structures can disproportionately privilege some voices over others, even within non-binary communities.

AVOID #5:

Reducing the complexity of non-binary individuals’ experience in an attempt to “avoid confusion” (Courvant 2011, 30).

Instructors may avoid incorporating the stories of non-binary individuals that disagree with one another in their syllabi because they fear confusing students. Focusing solely on the needs of the binary gender audience when constructing learning opportunities often results in an inattention to the needs of non-binary individuals in these teaching moments (Courvant 2011, 30). Instructors’ willingness to present conflicting viewpoints, and nuanced arguments, can offer students a worthwhile opportunity to consider course content more deeply.

AVOID #6:

Including non-binary topics and/or voices in separate unit(s) of a syllabus.

Instructors may incorporate non-binary topics and/or voices into a single unit of their syllabus. This approach often hinders students’ ability to think beyond the gender binary because this framing “reproduces normative assumptions about the dominance of some groups over others” (Valle-Ruiz et al. 2015). This occurs because students “visit” non-binary topics without being forced to engage the full complexities of social power and hierarchies that these topics highlight, and it doesn’t help students think through the way gender identity or expression intersects with other differences. A more ideal approach is for instructors to incorporate non-binary materials in multiple course topics and discuss the many questions that these materials provoke throughout a course (Preston 2011).

AVOID #7:

Including only a narrow range of non-binary topics in your syllabus.

Instructors may be inclined to include non-binary materials that exclusively focus on the negative experiences of marginalization that non-binary individuals face in their everyday lives. Abbott (2009) points to the importance of moving beyond depictions of transphobic violence and other bleak realities such as sexual assault, domestic violence and murder when incorporating non-binary experiences into course syllabi. Moving beyond this focus, Abbott explains, creates an opening to engage in conversations about fostering “greater tolerance, self-realization and equity” (2009, 160).

Effectively drawing connections between non-binary perspectives and broader course learning goals and objectives

In an effort to create more inclusive courses, instructors may elect to integrate authors with non-binary identities into their course. While integrating a wider array of voices is an important component of creating more gender-inclusive course content, doing so without giving full consideration to how these voices contribute to, and enhance the course learning goals is often confusing for students. Moreover, when the value of these additional voices is unclear, students may misdirect their attention and miss the learning potential.

Incorporating non-binary voices into course materials can be an important tool for unpacking students’ assumptions about gender identity and expression. However, it is essential that instructors include these texts with a clear sense of how they relate to the broader course objectives and goals. Moreover, it is imperative that instructors explicitly communicate these connections to students.

See the Vanderbilt Center for Teaching’s teaching guide titled “Difficult Dialogues” which provides instruction about how to think carefully about how difficult topics connect with your subject area and course learning goals.

In cases where students are unclear about the relevance of these readings to broader course goals, students’ existing assumptions about gender may be reaffirmed. Moreover, failing to account for how non-binary voices enhance course learning goals may actually hinder efforts to cultivate a more gender-inclusive classroom.

Integrating non-binary topics into courses that are seemingly unrelated to gender

Instructors in Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics (STEM) classrooms may believe that the content of the courses they lead are less amenable to acknowledging the fluidity of gender identity. Given this assumption, instructors in these disciplines may fail to fully consider the range of ways that gender identity affects the learning environment in classroom spaces.

For those who teach courses that are not explicitly related to themes of gender and identity, there are still opportunities to design gender-inclusive courses. This includes non-content related modifications such as (as recommended earlier in this guide):

- Adding an inclusivity statement that invites students to communicate their name and pronoun to the instructor and/or other students.

- Adding a brief explanation of the importance of mutual respect in learning spaces, particularly with respect to gender identity and expression.

However, there also may be opportunities to address gender inclusivity via course content creatively in multiple disciplinary contexts.

Some possible examples may include:

- In statistics classrooms, avoid binary male/female labels and/or discuss the limitations of such categorizations and the impacts it may have on understanding non-binary experiences.

- In business classrooms, include case studies for companies that develop products for non-binary clients.

- In engineering classrooms, encourage students to think about how existing technologies might require modification if one were to consider the needs of non-binary individuals.

- In biology classrooms, incorporate readings about the variation of gender identity and expression and variation in biological sex characteristics (for example when presenting on sex chromosomes).

- In medical school classrooms, incorporate materials about the specific medical needs of transgender and/or non-binary individuals within broader training about standards of care, developing an affirming bedside manner and obstacles to treatment in different segments of the population.

- In language classes that are gendered, include discussions about the impacts of gendered language use. This may include a discussion of binary gendered language and a discussion of the impacts of masculine gender as the default or universal. Discussions may include how various communities (e.g., feminists, LGBTQ+ groups) have historically and are currently responding to gendered language.

See the Vanderbilt Center for Teaching’s teaching guide titled “Grading Student Work” which includes a discussion of developing a grading criteria and providing meaningful feedback to students.

See a sample rubric created by CFT Assistant Director Joe Bandy.

Brondani and Paterson (2011) offer additional applications in dental education. Safer and Pearce (2013) provide empirical evidence that even small content changes can increase medical students’ comfort with transgender patients. Case, Stewart, and Tittsworth (2009) offer several recommendations for adapting

psychology course content that considers experiences of transgender people.

Implementing standard and fair assessment practices related to non-binary topics

Given the range of prior experiences with topics of gender identity, students may exhibit varying levels of expertise in how to identify credible sources, formulate rigorous arguments, and evaluate evidence used to examine claims related to these topics. In these cases, it is imperative that instructors clearly communicate course expectations and exhibit transparency in the method (and standards) of assessment.

Vanderbilt’s Name and Preferred Pronoun Change Policy

There are currently two name change options available to students at Vanderbilt.

- The first option is to submit an undocumented name change request. This option allows students to opt to have only their legal first and middle initials show in most university systems.

- The second option is to submit a chosen name request. This option allows students to specify a chosen name that appears in select internal university systems.

For more information about the name change process, please visit the Name Changes Policy Page of Vanderbilt’s K.C. Potter Center for Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer, & Intersex Life.

Additional Campus Resources

Continuum (Vanderbilt Psychological and Counseling Center) process-oriented therapy group for students wishing to give and receive support around sexual identity and/or gender identity.

LGBTQI Life Affinity Groups provide an affirming and brave space for Vanderbilt students to discuss their needs, challenges and successes.

Vanderbilt Trans Buddy Program provides emotional support to transgender patients during healthcare visits.

Trans@VU gathers information and resources related to gender identity and expression for the Vanderbilt community.

Vanderbilt Office of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer and Intersex Life cultural center and a place of affirmation for individuals of all identities, and a resource for information and support about gender and sexuality at Vanderbilt.

Resources for Basic Concepts and Definitions

Terms that describe people’s identities and experiences are constantly evolving. Additionally, individual people may use different definitions of the same term to describe their experiences and/or identities. Therefore, glossaries are neither comprehensive nor inviolable. Nonetheless, glossaries and working definitions of terms can help individuals enter conversations about promoting gender inclusivity. The following resources may be useful for people who want to learn about basic concepts and definitions relevant to gender and sexuality.

LGBTQI Life at Vanderbilt University – Definitions

GLSEN – Gender Terminology: Discussion Guide

References

Abbott, Traci B. 2009. “Teaching Transgender Literature at a Business College.” Race, Gender & Class: 152–69.

Brondani, Mario A., and Randy Paterson. 2011. “Teaching Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Issues in Dental Education: A Multipurpose Method.” Journal of dental education 75(10): 1354–61.

Case, Kim A., Briana Stewart, and Josephine Tittsworth. 2009. “Transgender across the Curriculum: A Psychology for Inclusion.” Teaching of Psychology 36(2): 117–21.

Clark, J. Elizabeth, Erica Rand, and Leonard Vogt. 2003. “Climate Control; Teaching About Gender and Sexuality in 2003.” Radical Teacher (66): 2.

Courvant, Diana. 2011. “Strip!” Radical Teacher (92): 26–34.

Levine, Sheen S., and David Stark. 2015. “Diversity Makes You Brighter.” The New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/2015/12/09/opinion/diversity-makes-you-brighter.html (April 11, 2016).

Phillips, Katherine W. 2014. “How Diversity Makes Us Smarter.” Scientific American. http://www.scientificamerican.com/article/how-diversity-makes-us-smarter/ (April 11, 2016).

Preston, Marilyn. 2011. “Not Another Special Guest: Transgender Inclusivity in a Human Sexuality Course.” Radical Teacher (92): 47–54.

Safer, Joshua, and Elizabeth Pearce. 2013. “A Simple Curriculum Content Change Increased Medical Student Comfort with Transgender Medicine.” Endocrine Practice 19(4): 633–37.

Schmalz, Julia. 2015. “‘Ask Me’: What LGBTQ Students Want Their Professors to Know.” The Chronicle of Higher Education. http://chronicle.com/article/Ask-Me-What-LGBTQ-Students/232797 (February 24, 2016).

Spade, Dean. 2011. “Some Very Basic Tips for Making Higher Education More Accessible to Trans Students and Rethinking How We Talk about Gendered Bodies.” Radical Teacher (92): 57–62.

Valle-Ruiz, Lis et al. 2015. “Course Design | A Guide to Feminist Pedagogy.” https://my.vanderbilt.edu/femped/habits-of-hand/course-design/ (April 7, 2016).

This teaching guide is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

1Many thanks to the following individuals for their helpful feedback and edits:

Dr. Melanie Adley, Dr. Joe Bandy, Dr. Richard Coble, Dr. Vivian Finch, Jane Hirtle, Corey Jansen, Liv N. Parks and Chris Purcell.

2Many thanks to Dr. Heather Fedesco and Dr. Joe Bandy for their helpful feedback and edits to the update.