Leveraging Travel Abroad: Collecting and Teaching with Authentic Resources

| by Stacey M. Johnson and Vivian Finch | Print Version |

| Cite this guide: Johnson, S. M. & Finch, V. (2016). Leveraging Travel Abroad: Collecting and Teaching with Authentic Resources. Vanderbilt University Center for Teaching. Retrieved [todaysdate] from https://cft.vanderbilt.edu/guides-sub-pages/authentic-resources/. |

Why is it important to have authentic resources in the classroom? | What is an authentic resource? | What kinds of resources will you collect when you travel abroad? | How do we collect these resources? | How do we use these resources in our teaching? | Resource Roundup

Your travel abroad makes you a better teacher and researcher. If students in your Nashville classroom were able to have those same travel experiences, their education would be enriched and their understanding refined. Unfortunately, your students may not have the opportunity to study abroad. How, then, can you bridge the gap? Authentic teaching resources collected abroad are one answer to that question. In this teaching guide, we will discuss:

Why is it important to have authentic resources in the classroom?

Having authentic resources in the classroom can support deeper student learning. However, without a plan for using them effectively, authentic resources on their own do not automatically lead to meeting learning objectives. That said, there are opportunities with authentic resources that are unique, and with careful planning, authentic resources can be a high-impact teaching practice. Some of those opportunities include the following:

→ Students can have a more intimate connection to the materials. They may personally know the people who collected them, or be the collectors themselves. That personal connection to the source can motivate students to make connections outside of the classroom and become self-directed in their learning.

→ When the materials are chosen by you for your own curriculum, the result is a highly tailored and relevant unit. With mass-produced materials, the content may need some adaptation to be relevant.

→ Many activities using authentic resources require students to become active contributors to the classroom and even make their work publicly available. Students become producers of knowledge rather than just passive consumers.

→ Among the more practical considerations is the issue of copyright. Because the instructor holds the copyright to such resources, both the instructor and students can freely remix and reuse such materials.

In light of such opportunities, instructors can plan learning experiences that make the best use of authentic resources.

How do authentic resources connect to and support deeper student learning? Students who actively engage with authentic resources in the classroom have the opportunity to gain knowledge and understanding of the discipline in ways that are otherwise difficult to recreate. First, students are able to see first hand what a research object in the discipline might look like, i.e. an authentic resource, and explore the methodology used to collect and analyze that object. Through carefully constructed classroom activities, students begin to become disciplinary practitioners by identifying what questions to ask (and not to ask) to yield useful analysis, engage in the process of analysis itself, and begin to develop disciplinary habits of mind, i.e. thinking like a historian, anthropologist, geologist, etc.1, Second, students who engage with authentic resources can create personal connections with the discipline that encourage and develop intrinsic motivation and, if given the opportunity, metacognition in their learning experiences. Finally, authentic resources can support and enhance effective pedagogical approaches and activities already in use in the classroom. By linking authentic resources in this manner, students can dig deeper in almost every aspect of the course, including collaborative activities, experiential activities, etc., thereby promoting students’ ability to meet learning objectives, especially those elusive enduring understandings.2

Click each tab to compare text book resources with authentic resources.

Text book |

Authentic resources |

| + Do not have to spend time and resources tracking down authentic materials, they are built in

– Resources are not tailored to your context or your audience |

+ May require initial time investment in collection/implementation, but generates longer-term payoff in |

Text book |

Authentic resources |

| + Resources never disappear (because of data loss, age, or decomposition)

– Resources persist and may not age well, become outdated |

+ Authentic resources collected by the instructor are permanently accessible regardless of textbook changes, and since the instructor is the author, continued availability is ensured. |

Text book |

Authentic resources |

| + Come with built in activities for engaging with those resources

– Activities may not line up with your own teaching preferences or your learners’ preferences |

+ Give you the opportunity to develop customized activities, employ signature pedagogies, or even give students control over learning activities |

Text book |

Authentic resources |

| + Everything is all in one place.

– Textbooks can be expensive, and can generally only be accessed by purchasing them. Moreover, textbooks are often only available in one medium. |

+ Because you own physical artifacts or the copyright to materials, you can determine the mediums for access and make them free of charge for students. |

What is an authentic resource? How do you know you are looking at one?

Authentic resources in the classroom consist of artifacts, documents, and media that give students a first-hand glimpse into the content of our course. These objects exist or are created with an authentic purpose, and are not primarily learning resources, rather we are re-appropriating them for the classroom.

Related to the concept of primary texts in a humanities course, but more inclusive, since an authentic resource can be primary texts, artifacts, samples, or even media created by others who are engaged in an authentic context. Some examples include videos created by travelers documenting a historical site, rock samples collected during field work, audio interviews conducted with locals while abroad, images of pottery unearthed in an archaeological dig.

We are borrowing the term “authentic resource” from the field of language teaching where it refers to any foreign language resource that is created by native speakers of the language for authentic purposes, rather than materials created for language learners for educational purposes. This teaching guides includes that definition of authentic resource and will be valuable for language instructors. However,instructors in many disciplines will find this information useful since we are also expanding the concept of authentic resource to include any representations of language, culture, history, or scientific inquiry that students in a classroom would normally not have access to. In this guide, our definition of authentic resources can vary according to a course or discipline, but will always refer to resources that:

- Represent a more authentic view of the course content than what is typically available in textbooks

- Are connected to real people’s experiences, either because they document someone’s experience or they give a glimpse into authentic experience in another place, or both

- Are being re-appropriated for educational purposes, even though that is not their original intent

What kinds of resources will you collect when you travel abroad?

Traveling abroad for research, to lead a study abroad, or for personal reasons can be an invaluable opportunity to collect authentic resources for your classroom. But how do you decide what to collect?

Disciplinary authenticity

Start by identifying what kinds of primary texts and artifacts are traditional to your discipline. For example, in a Classics classroom, images of preserved architectural structures, coins, or original texts such Caesar’s letters. Now, how can you enhance students’ experiences with these authentic resources or even collect previously unavailable resources during your travels abroad?

Instead of images of preserved architectural structures, you can give guided video tours of these sites. Instead of showing pictures of coins, you can bring coins to the classroom. In addition to reading a printed version of Caesar’s letters in a textbook, you can show images of the original letters from the museum.

Filling gaps in teaching

A second and important way to decide what authentic resources to collect is by starting with your course. What parts of your curriculum would benefit from the inclusion of authentic resources? Are there concepts or units where you wish student were developing a more authentic connection to course material? Are there natural overlaps between the travel that you will do and the courses that you teach? Do your students do any independent work or projects that would benefit from a more authentic perspective?

In a language course, you could consider collecting samples of authentic speech to supplement the course material (See figure 2). Lower-level language students may benefit from hearing how 3 or 4 different native speakers of a language answer the question “How are you today?” or “What was your favorite part of school when you were a child?”. These speech samples could be collected while abroad and then used in your classroom as part of language learning activities.

In a literature course, students may benefit from being able to visualize some of the places mentioned in the text (See figure 2). Images you collect while traveling could then be annotated and curated by students for public display. Using technology such as blogs, timelines, or GIS mapping software, students can make their project available to other students of the same work.

How do we collect these resources?

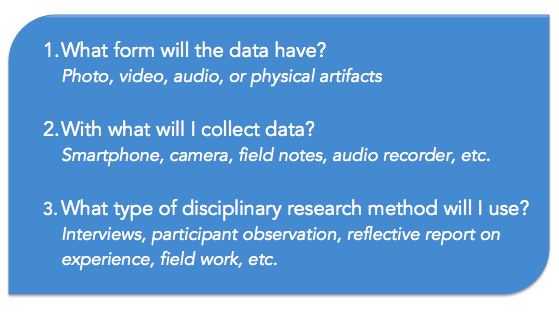

Once you’ve thought about what authentic resources you’d like to collect, you’ll want to consider a number of aspects of how to collect those authentic resources. The how of resource collection can often be just as important as the resource itself, as it impacts the ways in which students might interact with the resource. Here are three helpful questions to ask:

Much of what will inform the answers to these questions will draw from the authentic resources you would like to collect and the curricular gaps in your course that you would like to fill. However, you may also find that the answers to these questions may also impact the shape of the authentic resources you originally identified and the ways in which you sought to fill those curricular gaps. If you’re interested in crafting a plan for authentic resource collection, here is a useful worksheet to get you started.

If you need specific technologies in order to collect, store, or curate authentic resources, consider Center for Second Language Studies.

Once you have answered these central questions, you may also put some thought into how you will store the resources and make them available to students. Brightspace, Vanderbilt’s course management system, has several tools available that can help you organize, store, and make use of digital resources. Contact Brightspace support at the CFT if you would like to learn more about how to make good use of Brightspace. Brightspace is just one of many tools available to instructors. You might also consider a course blog, GIS, or a podcast (CFT podcast Part 1 and Part 2). You may find value in doing some exploration to see how others have incorporated the data collection and storage with their actual classroom uses. For example, we found papers on how faculty have integrated authentic resources through video tutorials3 or podcasts4.

When collecting authentic resources, there are also legal implications to consider, especially when data collection involves other people. Here are some resources to consider when your authentic resources fall into that category: consent and fair use. If you are planning on using student-generated authentic resources in particular, please keep FERPA in mind.

How do we use these resources in our teaching?

Once you have collected authentic resources, applying them in your teaching can be challenging. It is conceivable that you could end up with a shoebox full of artifacts or a thumb drive full of photos and videos, but not be able to find useful ways to share those resources with your students. Even if you chose the authentic resources based on how well they could fill a need in your syllabus, taking the integration of resources beyond a simple show-and-tell is challenging. Thinking of the classroom as a constructivist, collaborative space and using active learning techniques can lead to useful ideas for implementing these authentic resources.

If you are wondering how to successfully integrate these resources into your teaching, here are two strategies that will work with most resources and most classes.

Experiential learning cycle

Kolb’s experiential learning cycle5 describes the steps learners take as they make sense of experience. This tool is most useful for understanding learner experiences. However, we find it to be a useful framework for organizing learning with authentic resources. When we follow the experiential learning cycle, we walk students step-by-step through reflective, abstract, and experimental activities related to our authentic resources, ensuring maximum impact from the resources.

This format works best as a project or multi-day activity that spans both in-class and at-home work. Students will interact deeply with a complex resource or collection of resources over a period of time, connecting their learning to the learning objectives for the course.

As you can see in the Kolb’s Experiential Learning Cycle figure below, learning begins with a Concrete Experience. In this case, the concrete experience will be the examination of or interaction with an authentic teaching resource. Then, students will move into a stage of Reflective Observation, comparing the resource to their own ideas, experiences, and feelings. The third step in the cycle is where the instructor most often plays a primary role. In the Abstract Conceptualization stage, students make connections between the experience/authentic resource and broader issues, ideas, and theories. Finally, in the Active Experimentation stage, students are encouraged to interact in a new way with the resource, or to create an experience or resource of their own based on their deep understanding of the original Concrete Experience. The figure you see here lists some possible activities in each of these stages

Think/Pair/Share

Think/Pair/Share (TPS) is a commonly used group work technique to guide class discussions in larger classes. It allows students to work through questions or resources on their own and with a small group, and then hear from a variety of voices in the class as well. This technique has a close connection to the language assessment technique known as IPA (Integrated Performance Assessment). The difference is the scope at which each technique can be executed. An IPA is a method of organizing instruction that moves through the interpretive, interpersonal, and presentational modes of communication. An IPA will usually require multiple class periods to do well. However, TPS can take as little as a few minutes, while requiring the same sorts of skills as an IPA. Think of TPS as a micro-unit of integrated performance assessment. An IPA gives teachers an excellent venue for using authentic teaching resources in the classroom, but a TPS can act as a venue for incorporating multiple resources into a single class period. For instance, when you have resources that you want to use as examples of language or culture in a single class period, or to illustrate a single point within a larger lecture/discussion, this can be a way to get students actively engaging with a resource on a small scale. You could project a photo or video on the classroom screen and ask students a reflective or probing question about the content. Then, students would get 2 minutes to think of their own answer and jot down responses, followed by 3 minutes to talk with a small group about their answers, followed then by 4 minutes for groups to report their ideas and discuss the question as a whole class.

While the possibilities for using authentic resources in the classroom are endless, the two techniques outlined above will give instructors a useful starting point for effectively integrating them into the classroom. If you would like more ideas on how to leverage authentic resources in your classroom, consult our Resource Roundup below.

How can we engage students in the collection and implementation process?

If you’re interested in taking the next step and involving students in the collection and implementation process, please consult our upcoming book chapter on Authentic Resources.

Resource Roundup

The CFT has a large selection of teaching guides on specific topics related to teaching with authentic resources. There are also many places across campus where faculty can find support.

- Effective Educational Videos

- Visual Thinking

- Group Work

- Metacognition

- Motivating Students

- Teaching Outside the Classroom

- Classroom Assessment Techniques

- Active Learning

Specific technology tools you may want to use:

- Brightspace, Vanderbilt’s course management system. Brightspace support at the CFT provides Brightspace users across campus with the support they need to make the best use of the available tools on our course management system.

- Course blogs through Vanderbilt’s WordPress installation or through another service

- GIS or Geographical Information Systems software can annotate maps with images, text, video, and any other digital resource

- Podcasting (CFT podcast Part 1 and Part 2)

- Wikis, Box, Google docs or other collaborative web document

Additionally, the CFT offers one-on-one consultation services ranging from course design to on the ground teaching approaches to help you plans as you collect and leverage those authentic resources for classroom use. For information, please consult the CFT website.

If you want to create professional quality video content, you may want to contact CFT’s Digital Media Specialist, Carly Byer. She runs the CFT’s One Button Studio where faculty can easily record high quality videos without any prior video experience. The CFT also has simple to use Take and Try Resources, available for faculty to checkout.

If you want to do more research on how foreign language instructors at Vanderbilt are using authentic resources in the classroom or learn how to leverage specific educational technology for the foreign language classroom, please contact the Vanderbilt Center for Second Language Studies.

1Gurung, R. A. R., Chick, N. L., & Haynie, A. (2009). Exploring signature pedagogies: Approaches to teaching disciplinary habits of mind. Sterling, Va: Stylus Pub.

2Wiggins, G. P., & McTighe, J. (1998). Understanding by design. Alexandria, Va: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

3Goodenough, A., MacTavish, L., Hart, A. (2013). Developing a Supportive Framework for Learning on Biosciences Field Courses through Video-Based Resources. MERLOT Journal of Online Learning and Teaching, 9(3).

4Lee, M., McLoughlin, C., Chan, A. (2008). Talk the talk: Learner-generated podcasts as catalysts for knowledge creation. British Journal of Educational Technology, 39(3), 501–521.

5Kolb, D.A. (1984). Experiential learning: Experience as the source of learning and development. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

This teaching guide is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. Photo Credit

Cite this guide:

Johnson, S. M. and Finch, V. (2016). Leveraging Travel Abroad: Collecting and Teaching with Authentic Resources. Retrieved [todaysdate] from https://cft.vanderbilt.edu/leveraging-travel-abroad-collecting-and-teaching-with-authentic-resources/.