Making Student Thinking Visible: Metacognitive Practices in the Classroom

by Nancy Chick (CFT Assistant Director) and Katie Headrick Taylor (CFT Graduate Teaching Fellow)

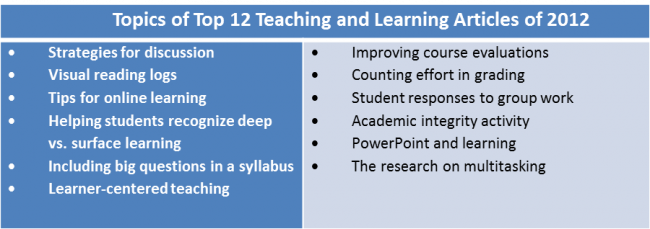

Every Friday, the four CFT Graduate Teaching Fellows and Assistant Director Nancy Chick meet to discuss the week’s activities and then explore something substantive, either through readings or guests. We recently discussed the “Top 12 Teaching and Learning Articles of 2012” published by Faculty Focus, a website and e-newsletter that regularly publishes articles on teaching and learning.

The topics of these 12 articles are so varied that Nancy thought it would open up plenty of possibilities for discussion and future exploration, as well as inform the day-to-day consulting work we do at the CFT. However, Katie started the discussion by pointing out that a theme bound these varied articles together, metacognition—or thinking about one’s own thinking. Thanks to the wealth of research by cognitive psychologists, education researchers, and scholarship of teaching and learning (SoTL) researchers, we know that making student thinking visible to them is one of the best approaches we can implement in the classroom (Bransford, Brown, & Cocking, 2000, Tanner, 2012; Resnick, 1987; Collins & Ferguson, 1993).

Katie found that many of the “Top 12” articles identified strategies for making student thinking visible not to just instructors, but also to their own learning processes. By intentionally uncovering how learners were thinking about discipline-specific concepts, students and instructors were able to discuss the ways in which this thinking was similar or different to the thinking of disciplinary experts. Contemplating the epistemological question of “how do we know what we know?” brought novice thinking into contact with more sophisticated, expert ways of thinking within the discipline. Working at this metacognitive interface (where expert and novice thinking come together) modeled for students disciplinary habits of mind, or how students should be thinking and learning about the content. As Barbara Y. White and John R. Frederiksen (1998) state,

“Creating curricula that help students to develop an awareness of their inquiry process and an ability to reflect on it could enable students to improve their learning expertise while also acquiring subject matter expertise” (p. 4).

Nancy was impressed: not only did this thematic connection of metacognition show some insightful reading; it also suggested good news for teaching and learning. The “Top 12 Articles” were selected not for their quality but for their popularity, “based on a combination of the number of reader comments and social shares, e-newsletter open and click-thru rates, web traffic and other reader engagement metrics.” If these articles were widely read, and the principles of metacognition run through many of them, then readers were not only learning about strategies for discussion, learner-centered teaching, teaching academic integrity, and the like: they also got a stealth education on metacognition.

In “Using ‘Frameworks’ to Enhance Teaching and Learning,” Patrice W. Hallock explains how she uses three shapes as “a writing space to record what students are thinking about course content as well as how they are thinking about it.” It’s a simple strategy. Students note “Something that ‘squares’ with my beliefs” in the shape of a square, “3 points to remember” in a triangle, and “A question circling in my mind” in a circle after they’ve read a course text. While these prompts may not apply across disciplines, the strategy is elegantly simple: develop a few easy-to-remember metacognitive prompts to develop a habit in the students’ post-reading moments. Hallock offers a few more examples created by her own students, who used metaphors instead of basic shapes. One used archery with prompts about “’Bullseye’ beliefs” or ideas,” “Material that missed the mark,” “overarching concepts,” and concepts that “still need sharpening.” Another drew a camera with prompts for “Concepts to FOCUS on,” “Ideas that need further DEVELOPment,” and so on. As her original strategy is memorable in its language of the three shapes, these student-generated examples are memorable in their metaphors—and this ease of memory facilitates the habit-formation of such questions about what the student learned (or didn’t) from the reading.

In her article, “Five Characteristics of Learner-Centered Teaching,” Maryellen Weimer suggests that teachers have to teach students much more than the content or the big ideas of the discipline. Teachers have to

“teach students how to think, solve problems, evaluate evidence, analyze arguments, generate hypotheses – all those learning skills essential to mastering material in the discipline.”

But while instructors should make a concerted effort to model appropriate ways of thinking, they should also give students space to grapple with and reflect on the material on their own. A part of this thinking space should include a reflection on their learning process, “like how they study for exams, when they do assigned readings, whether they revise their writing or check their answers.” Having time and space to analyze their thinking process allows students to develop a deeper awareness of their own learning strengths and weaknesses and be able to compare these qualities to the great thinkers they may want to emulate.

Weimer’s article “Deep Learning vs. Surface Learning: Getting Students to Understand the Difference” spotlights a project in which the instructor identified for students “deep” or “cognitively active learning behaviors” and surface or “cognitively passive learning behaviors” and then had students monitor and report their study strategies throughout the semester. Students who participated in this monitoring-reporting activity had higher exam scores than those who didn’t.

Weimer’s article “Deep Learning vs. Surface Learning: Getting Students to Understand the Difference” spotlights a project in which the instructor identified for students “deep” or “cognitively active learning behaviors” and surface or “cognitively passive learning behaviors” and then had students monitor and report their study strategies throughout the semester. Students who participated in this monitoring-reporting activity had higher exam scores than those who didn’t.

Barbi Honeycutt’s “A Syllabus Tip: Embed Big Questions” simply advises us to consider our course learning outcomes, develop questions based on those outcomes, and put them throughout our syllabus to “stimulate discussion, create curiosity, and assess students’ knowledge.” Such larger questions can also be seen as metacognitive, encouraging students to think above and beyond basic course content to how it connects to broader issues and disciplinary goals. Being explicit about the purpose of these questions helps students recognize that they’re practicing expert thinking.

As you read the remaining articles, consider how they promote metacognition.

For more information on metacognition, including more specific ways to implement it across the disciplines, read CFT Assistant Director Cynthia Brame‘s blog post “Thinking about Metacognition,” and stay tuned for the CFT’s “Metacognition” teaching guide written by Nancy Chick, coming soon.

References

- Bransford, J.D., Brown, A.L., & Cocking, R.R. (2000). How people learn: Brain, mind, experience, and school. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press.

- Collins, A., & Ferguson, W. (1993). Epistemic forms and epistemic games: Structures and strategies to guide inquiry. Educational Psychologist, 28, 25-42.

- Hallock, P. W. (2012). “Using ‘frameworks’ to enhance teaching and learning.” Faculty Focus. [Web log]. Retrieved from http://www.facultyfocus.com/articles/teaching-and-learning/using-frameworks-to-enhance-teaching-and-learning/.

- Honeycutt, B. (2012). “A Syllabus tip: embed big questions.” Faculty Focus. [Web log]. Retrieved from http://www.facultyfocus.com/articles/instructional-design/a-syllabus-tip-embed-big-questions/.

- Resnick, L. (1987). Education and learning to think. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

- Tanner, K. D. (Summer 2012). Promoting student metacognition. CBE—Life Sciences Education. 11. 113-120.

- Weimer, M. (2012). “Deep Learning vs. Surface Learning: Getting Students to Understand the Difference.” Faculty Focus. [Web log]. Retrieved from http://www.facultyfocus.com/articles/teaching-professor-blog/deep-learning-vs-surface-learning-getting-students-to-understand-the-difference/.

- Weimer, M. (2012). “Five characteristics of learner-centered teaching.” Faculty Focus. [Web log]. Retrieved from http://www.facultyfocus.com/articles/effective-teaching-strategies/five-characteristics-of-learner-centered-teaching/.

- White, B.Y., & Frederiksen, J.R. (1998). Inquiry, modeling, and metacognition: Making science accessible to all students. Cognition and Instruction, 16(1), 3-118.

————

Leave a Response