Love of Hebrew and Yiddish leads Allison Schachter to hidden stories of women authors

Allison Schachter, an associate professor of Jewish studies, English, and Russian and East European studies, never intended to end up in her current field. After studying French and Hebrew as an undergraduate, she entered graduate school for comparative literature and planned to focus on seventeenth-century drama. But her love of learning new languages repeatedly drew her back to Hebrew and Yiddish. At Vanderbilt since 2006, she’s now the chair of the College of Arts and Science’s Jewish Studies department.

“The questions of modern Jewish culture, of Jewish identity and social justice, just kept resonating with me, and I kept coming back to them,” she said. “I ended up writing my dissertation on Hebrew and Yiddish literature.”

Given that history, the serendipitous nature of her current research seems appropriate. Schachter’s first published book was about Jewish modernism. She originally intended to organize her second book around the same topic, with a focus on how modern Jewish authors dealt with questions of gender and sexual identity. As she researched the subject, however, she came to a startling realization: though scholars have regularly published on Yiddish poetry, there was almost no research on Yiddish women’s prose fiction.

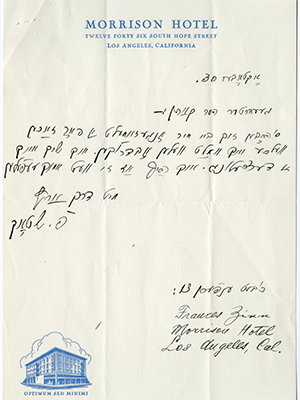

This epiphany came to Schachter as she was leafing through a literary journal she’d discovered. Founded by a group of Jewish women intellectuals in what was then the Galicia region of the Austro-Hungarian Empire (now located in Poland), the journal contained a review of short stories by an author named Fradl Shtok. Schachter had read Shtok’s poetry but had not known about the author’s short fiction. This led her to begin researching, reading, and translating Yiddish women’s prose fiction—an endeavor that made her realize there were many authors whose histories had been erased or hidden.

“I thought, ‘Who are these women, and why haven’t I read them?’ I had this gap in my education, but I hadn’t noticed it,” Schachter said. “I think so many of us know about culture and intellectual history through the lens of male authors, but women’s texts are there, even though they’re not often considered canonical.”

Schachter decided to shift her focus to Jewish women authors who were active between the first and second world wars. She researched their personal stories and the challenges they faced as outsiders in the fields of translation, literature, and intellectual thought. Many of them endured both figurative and literal violence for daring to break with social norms, and they often died as outcasts or in poverty. Shtok, for instance, lived out her final years in obscurity in a psychiatric institution. Historians wiped out at least ten years of her life, saying she had died a full decade or more before she actually did. Yet Shtok and her contemporaries managed to sustain an active, transnational community that tackled the major political and intellectual issues of the day.

“They were avant garde writers who asked the big questions in really different and interesting ways than the canonical texts we rely on to describe this moment. They were thinking about Jewish nationalism and socialism, and they brought their feminist lens to the political and artistic worlds,” Schachter said.

Over the course of writing her book, Schachter developed a new theory to set against the typical narrative about Jewish history and culture of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. According to Schachter, scholars of the period typically frame it as the era of when “Jews became men.” Europeans often belittled Jews as “effeminate,” and modernist historians tend to focus on how Jewish men fought back against that stereotype through movements such as Zionism, which projected power and masculinity. But Schachter found that the modern period was also one during which women made lasting and meaningful contributions to Jewish culture and history—even if the sources of those contributions were later buried from view. By bringing them back into the light, Schachter hopes to remind others that canons can be incomplete, and that we miss out on key insights when we leave them that way.

“Ultimately, it’s not enough just to recover women’s voices. We also have to rewrite or rethink history after we read these women,” she said. “Their perspectives should actually change how we understand history.”

Schachter will publish two books with Northwestern University Press in December: Women Writing Jewish Modernity, 1919-1939 and A Woman From the Provinces: The Selected Stories of Fradl Shtok.