Study reveals role giant ground sloths played in the environment, potentially aiding in ecological restoration today

Adapted from an article by Andy Flick

When you think of a sloth, an image of a slow, cuddly, furry creature hanging out in trees may come to mind—the picture of tranquility. But millions of years ago, sloths were around 9 feet tall and weighed anywhere from 400-2,500 pounds.

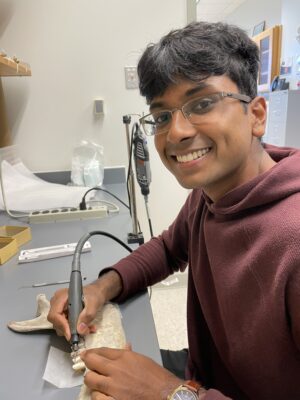

A new study led by Aditya Kurre, BA’22, and Associate Professor of Biological Sciences and Guggenheim Fellow Larisa DeSantis has revealed the specific diet of two species of giant ground sloth, uncovering the vital roles they played in their environments. Their findings could help scientists restore ecosystems that once thrived thanks to these massive mammals.

“When we think about modern sloths, we think of lethargic, gentle creatures,” Kurre said. “And while it is hard to imagine that their ancestors were some of the most gigantic and diverse mammals to inhabit the Western Hemisphere, layers of evidence show us that their diets and behaviors reflected these characteristics.”

The study, published in Biology Letters, used dental analysis to reconstruct the ancient diets of theShasta ground sloth and Harlan’s giant ground sloth. The team made molds of fossil teeth, created clear casts, and scanned them under a 3D microscope. Computer software measured tiny scratches and pits that act as dietary fingerprints and reveal what these animals were really eating thousands of years ago.

“Sloth teeth do not have enamel like ours do, which makes them tricky to study,” DeSantis said. “But by focusing on the dentin layer, we can still see microwear textures and compare them to living sloths that primarily eat leaves and closely related armadillos that are primarily insectivorous.”

This research stemmed from Kurre’s interest in what teeth can uncover about the ancient past, which was the topic of his Immersion Vanderbilt project.

The findings revealed that while the Shasta ground sloth likely ate leaves and woody materials, Harlan’s ground sloth ate hard foods, such as tubers, roots, seeds, and fungi. This, coupled with their large claws and the shape of their shoulder bones, suggest that they likely served a large role in helping to disperse plants and fungi, as well as transport seeds and spores across large distances. These were services that no other species fully replaced, and these findings could help researchers restore the diversity and strength of these ecosystems.

The extinction of the giant ground sloth reminds us that when we lose species, we also lose the ecological services that keep ecosystems functioning.

“Studying the past is critical to understanding what we have lost,” DeSantis said. “There is a famous song lyric by Joni Mitchell that says, ‘You don’t know what you’ve got ’til it’s gone.’ Similarly, we often don’t know what has changed, especially if those changes occur over decades, centuries, or in this case millennia, unless we study the past. If we want to have healthy ecosystems, we need to know how best to restore them, including figuring out if there are any missing services that once helped ecosystems thrive.”

Read the full paper in Biology Letters.