The big picture: Archaeology of the Andes revealed on a scale not previously seen

Steven Wernke, associate professor and chair of anthropology, has developed GeoPACHA (Geospatial Platform for Andean Culture, History and Archaeology), a web application that allows researchers to map archaeological sites in the Andes at a greater scale than ever before. GeoPACHA has enabled new discoveries about past human occupation in the region. These findings will be featured six articles in the February issue of the journal Antiquity.

“One of the biggest challenges in archaeology is aligning the scales of our datasets with those of the social worlds that we seek to study,” said Wernke. “When archaeologists are asked big picture questions about the human past—for example,about the size of the populations of ancient empires or the effects of past climate change on settlement patterns across a continent––it is very hard, if not impossible, to answer them through conventional archaeological methods, because the scale of the phenomena far surpass what we can directly observe in the field.”

Wernke and his colleague Parker VanValkenburgh of Brown University developed GeoPACHA to address these kinds of large scale problems, and it has now been used by teams of archaeologists to examine a large swath of the Peruvian Andes.

GeoPACHA allows international teams of regional experts and archaeology students to examine high resolution satellite imagery to map and describe archaeological sites in systematic fashion. The features are then independently assessed for accuracy, through a two-tiered review and editing process. This allows survey to be wide- ranging, without compromising on the quality of the data. It also enabled researchers to collaborate through the pandemic, when fieldwork was not feasible.

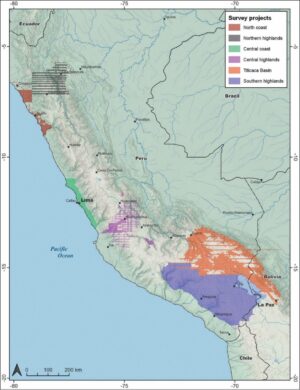

In this first stage of the project, six different teams used GeoPACHA to collect data and address a diverse series of independent research questions about the history of the Peruvian Andes.

Giles Spence Morrow, a Vanderbilt anthropology postdoctoral fellow who collaborated on the research, was the lead writer on one of the Antiquity articles describing how the GeoPACHA survey was used to examine hilltop fortifications on the north coast of Peru. While parts of his study area had already been surveyed on foot, previous researchers have tended to miss sites located in remote and hard-to-access areas. Using GeoPACHA allowed researchers to efficiently map these sites, which in turn helped to eliminate accessibility bias from the survey dataset.

“The availability of high-resolution imagery of such difficult-to-reach areas has proven to provide a significant increase in site identifications,” said Morrow.

GeoPACHA’s usefulness as a tool for systematically mapping remote sites is highlighted by another of the articles, focusing on the central coast, where oases known as lomas were a common focus of human activity in the past, while another of the articles examines an area of more than 150,000 km2 in the south-central highlands, a project that mapped over 1100 hillforts called pukaras, which were widespread in that region during the Late Intermediate Period (AD 1000-1450). Using GeoPACHA, the team found that pukaras were distributed in clusters of different sizes and configurations, which appear to reflect distinct kinds of defensive networks and “defensive logics.”

Reflecting on the surveys as a whole, Wernke and VanValkenburgh note that it is remarkable how much of the overall

survey area was not densely populated. Around 95% of the southern Peruvian highlands contain no obvious archaeological features, suggesting that Indigenous Andean economies were adapted to highly specific conditions, including rainfall and topography, rather than being evenly spread across the landscape.

“Because many of these areas are also not currently inhabited and are difficult to reach, they are also places where field-based surveys are less likely to be conducted,” said Wernke. “As a result, our models of settlement distribution were biased in favor of densely inhabited areas. GeoPACHA addresses this bias by providing continuous distributional views across regions.”

GeoPACHA is now poised to expand coverage even further, through the application of AI-based deep learning models trained on data collected in GeoPACHA, which has been awarded a three-year grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities to Wernke, VanValkenburgh, and their Vanderbilt colleague, Yuankai Huo, assistant professor of computer science.

In another special section article, James Zimmer-Dauphinee, a postdoctoral fellow in anthropology, presents preliminary results from applications of AI deep learning models to project data. He argues that manual surveys are time-consuming and can be monotonous, but completely automated surveys are often inaccurate. He proposes an alternative model, ‘human-machine teaming’ in which deep-learning models filter out areas without archaeological features, allowing surveyors to dedicate their time to high-probability zones. These approaches are particularly useful in areas like the South Central Peruvian Andes, where 95% of areas surveyed were devoid of features.

“We envision a near-term future in which human-machine teaming approaches will surpass the sensitivity and specificity rates of either approach when deployed exclusively,” said Zimmer-Dauphinee. “Could this combination of humans and AI be the future of archaeology?”