Renã Robinson: Helping others through the power of research and representation

For Associate Professor of Chemistry Renã Robinson, science has long been about helping people. She was an avid scientist-in-training throughout her childhood and went to college intending to become a cardiac surgeon. But when she got close to the end of her undergraduate career, she said, “I realized I just didn’t have another 12 years of training in me.” Thankfully, she had majored in chemistry—a field that provides excellent preparation for medical school but also has broad applications elsewhere.

She considered becoming an entrepreneur and applied to graduate school to learn the chemistry of personal-care products, so she could start her own beauty company. Then a combination of circumstances pointed her in a different direction. At the same time that her mother was working as a caregiver for Alzheimer’s patients, Robinson joined a lab that was using mass spectrometry to study aging in fruit flies.

“I realized I was really good at generating data, and I decided that I wanted to know more about what my data meant and how I could use it to help people,” Robinson said. “Then it dawned on me that my mom’s work was connected with what I was doing in grad school.”

She decided to pivot once again, this time to become an Alzheimer’s disease researcher. As she progressed in her work, she made a surprising—and disturbing—discovery. Alzheimer’s disease is twice as prevalent among Black Americans as among white Americans, and Robinson began to suspect that the gap stems at least partly from the physical stress caused by systemic racism and the prevalence of other conditions, such as hypertension.

According to Robinson, trauma and discrimination can create an inflammatory response in the body, raising rates of disease and shortening lifespans. Her lab uses mass spectrometry to look for molecular-level, biological changes that are associated with these negative health outcomes. The goal is both to educate the scientific community about the need for increased representation in basic science research and to understand disparities in ways that will support the development of more effective therapies for a devastating disease.

Robinson also has another goal: to increase representation in STEM and in scientific research, especially in her own field of chemistry. One of the College of Arts and Science’s most influential mentors and a Dorothy Wingfield Phillips Chancellor’s Faculty Fellow, she channels her passion for helping others into creating a nurturing lab environment for trainee scientists from underrepresented groups. “They bring life to the lab, and I get to learn a lot from them,” she said. She also recently won a National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant to help increase Alzheimer’s disease research participation by Black Americans, who are profoundly underrepresented in studies.

Robinson also has another goal: to increase representation in STEM and in scientific research, especially in her own field of chemistry. One of the College of Arts and Science’s most influential mentors and a Dorothy Wingfield Phillips Chancellor’s Faculty Fellow, she channels her passion for helping others into creating a nurturing lab environment for trainee scientists from underrepresented groups. “They bring life to the lab, and I get to learn a lot from them,” she said. She also recently won a National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant to help increase Alzheimer’s disease research participation by Black Americans, who are profoundly underrepresented in studies.

The effort to increase representation in STEM, Robinson believes, is one of the biggest and most crucial challenges facing the natural sciences—whether in research topics and subjects, in the classroom, or behind the lab bench. Where chemistry is concerned, she said, the issue is twofold. In addition to recruiting more underrepresented students to study chemistry, Robinson said that universities and industry need to remove barriers that prevent underrepresented scientists from excelling and staying in the field once they become chemists.

In part, this focus on representation is why Robinson believes Black History Month is important: it’s an opportunity to celebrate the stories of trailblazing scientists who have broken through barriers and positively impacted Americans today. “I hope that we eventually don’t need Black History Month because those stories are just integrated into the fabric of our daily lives and our education system,” she said. Until that happens, however, she hopes people will seize the chance to start uncomfortable conversations and educate themselves about things they realize are unfamiliar.

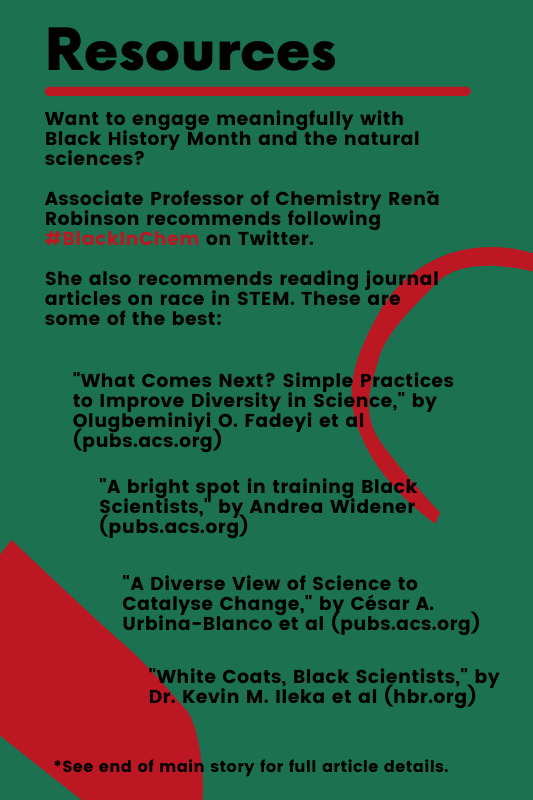

The national conversation often centers around toxic social media, misinformation, and information overload. But, as Robinson points out, online platforms also provide unprecedented access to the movements, thinkers, research, and conversations that can help to upend systemic racism and its ugly effects. The end result will benefit everyone.

“We all lose out if underrepresented groups can’t bring their talent to the table,” she said. “There are really important problems in the world, and they require all our voices to solve them.”