New Political Science Research Debunks Myths About White Working-Class Support for Trump

New research from Associate Professor of Political Science Noam Lupu challenges several common assumptions about white working-class support for President Donald Trump. Lupu conducted the research, outlined in the article “The White Working Class and the 2016 Election,” with Duke University’s Nicholas Carnes. The two first met in graduate school and have since collaborated many times on research concerning class, political office-holders, and voting patterns.

Carnes and Lupu’s article addresses four assumptions often made about white working-class voters in the 2016 presidential election: (1) most of the people who voted for Trump in 2016 were white working-class, (2) most white working-class voters voted for Trump, (3) white working-class voters switched from Obama to Trump at unusually high rates, and (4) white working-class voters were crucial to Trump’s victory in swing states. According to Lupu, he and Carnes decided to investigate these assertions after noticing that they had migrated from mass-media usage to academic writing, where many researchers were treating them as truisms.

“Having done this work for a number of years, we had a sense of the biases and narratives that are out there about class and about how people from different classes behave politically. We started seeing these ideas in academic papers, where people were taking for granted that the white working class is why Trump is in office, so we decided to do something more rigorous, a deeper dive,” Lupu said.

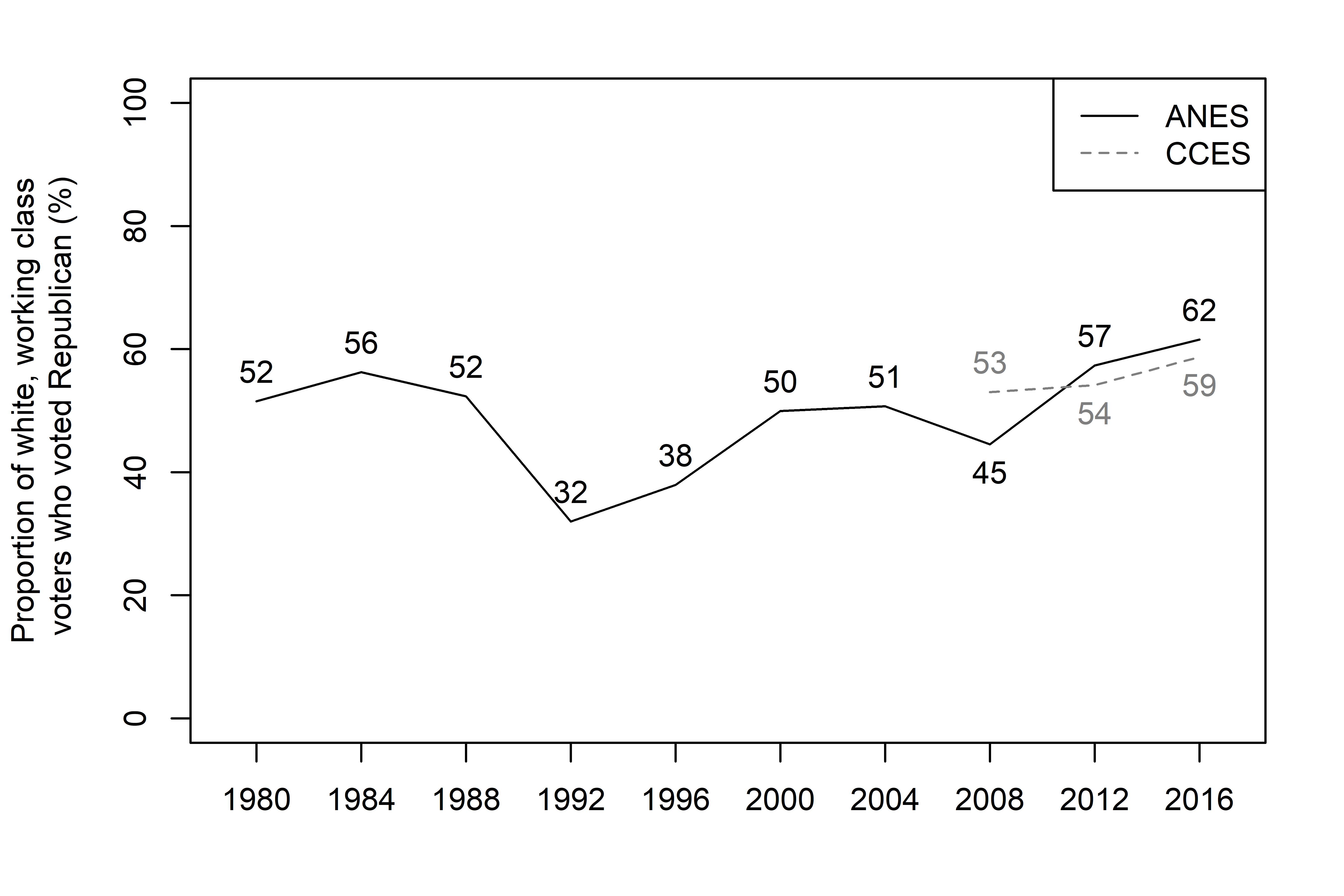

Starting with survey data from the 2016 election and then working farther back, they conducted their own analyses to determine the truth of those key assumptions. One was simply wrong: only about 30 percent, not a majority, of Trump’s supporters were white working-class. A related assertion, however, was true: of white working-class voters, most (about 60 percent) did indeed support Trump. Nevertheless, Lupu said, the statistic has taken on a misleading significance. He typically sees it cited as proof that, compared to previous Republican candidates, Trump appealed uniquely to white working-class voters—possibly because of his rhetoric or policy positions. In reality, Trump demonstrated broad appeal among Republican voters. Moreover, the white working class has been increasingly voting Republican since 1992, and 2016 support for Trump was in line with that trend.

The remaining two assumptions also fell apart under close scrutiny. In examining the assertion that white working-class voters switched from Obama to Trump at unusually high rates, Lupu and Carnes looked at data from voters who were interviewed immediately after voting: first in 2012, then again in 2016. They found that rates of switching among white working-class voters were actually in line with rates of Democrat-to-Republican switching in previous elections (for instance, of voters who supported Al Gore in 2000 but switched to George W. Bush in 2004). The fourth assumption—that white working-class voters “swung” certain states to Trump—was problematic on multiple fronts. First, Lupu and Carnes found that the claim couldn’t be validated empirically in many cases, due to small sample sizes in individual states and the fact that multiple demographics of Trump supporters (not just the white working class) were large enough to “swing” certain states in his favor. Where a state’s sample size did allow for empirical analysis of the claim, Lupu and Carnes found that Trump commanded similar levels of white working-class support in both swing and non-swing states. Furthermore, in states won by Trump, the percentage of Trump supporters who were white working class generally tracked with the overall percentage of voters in that demographic.

Ultimately, Lupu and Carnes concluded that these key assertions are not only mostly inaccurate, but they distract researchers from discovering the true reasons behind Trump’s 2016 victory and the support he enjoyed among white working-class voters. Lupu and Carnes suspect that those reasons really lie in the overall trend they uncovered: since 1992, white working-class voters have increasingly supported Republican candidates, though Lupu and Carnes are not yet sure why.

“If we’re really going to understand what happened in 2016, we have to understand what happened before that. We need to take a longer view,” Lupu said. “Every election night, we sort of have this idea that everything is completely different. Trump’s election was certainly a more surprising outcome because he is a very unconventional politician. But what underlies his victory has been going on for a while.”