Biological Sciences Ph.D. Student Finds Creative Outlet in Science-Themed Art

It’s no surprise that Jacob Steenwyk became interested in art at a young age. Both his parents are artists: his father served as art director for the Los Angeles Dodgers, and his mother was a recognized art critic who has published in major magazines in the Philippines. Steenwyk loved making art as a child and was an avid musician in high school. As an undergraduate, however, he discovered a love for science and has creatively figured out how to blend his two passions. Now entering his fifth year of Ph.D. studies in the College of Arts and Science’s Department of Biological Sciences, Steenwyk feeds his creative side by making science-themed art.

Science first caught his attention at Clark University in Worcester, MA. “I started college with the lofty goal of trying to understand the world around me,” Steenwyk says. “I took psychology thinking it would provide me with the answers I was looking for, but I realized what I really wanted to understand was the natural world around me. That’s when I started taking biology classes.”

He also started hiking in the forests of Massachusetts, a landscape dramatically different from that of his Southern California hometown. On his hikes, he often noticed the unfamiliar varieties of mushrooms growing on the forest floor. They piqued his interest in fungi, and he went on to earn his master’s degree in the subject. His thesis adviser at Clark, John G. Gibbons, had studied with A&S Professor of Biological Sciences Antonis Rokas. So, when Steenwyk decided to earn his Ph.D., joining Rokas’s lab at Vanderbilt was the logical next step.

Steenwyk’s current research with Rokas has two primary lines of inquiry: the evolution of pathogenic fungi and that of budding yeasts, a subtype of fungi. The first subject is especially relevant in today’s environment, since pathogenic fungi can cause lung disease that may complicate illnesses such as COVID-19. Recently, Steenwyk and Rokas found that a pathogenic species of Aspergillus, a type of fungus they study, originated from the hybridization of two other species and appears to be linked to lung disease. It’s the first known case of a hybrid Aspergillus mold infecting humans.

For their second line of inquiry, Steenywk and Rokas are collaborating with the University of Wisconsin-Madison’s Hittinger Lab on a project they call Y1000+: the Herculean task of sequencing and analyzing the genomes of all 1,000-plus species of budding yeasts. “Yeasts are pillars of multiple scientific fields. We want to capture their diversity and understand what drives it,” Steenwyk said.

Beneficial fungi include baker’s yeasts and brewer’s yeasts: those commonly used in making wine, beer, bread, cheese, and other food and drink. Drug manufacturers also use yeasts in bioreactors to help produce insulin, which previously had to be harvested from pigs. On the other hand, some yeasts are pathogenic and can cause infections of varying severity. Steenwyk and Rokas hope that findings from Y1000+ will not only help optimize yeast’s beneficial uses, but also support the development of therapies to fight pathogenic fungi. So far, Steenwyk has discovered through the sequencing project that a certain line of yeasts has lost numerous cell cycle and DNA repair genes over time—an evolutionary outcome strikingly similar to what happens in cancer cells.

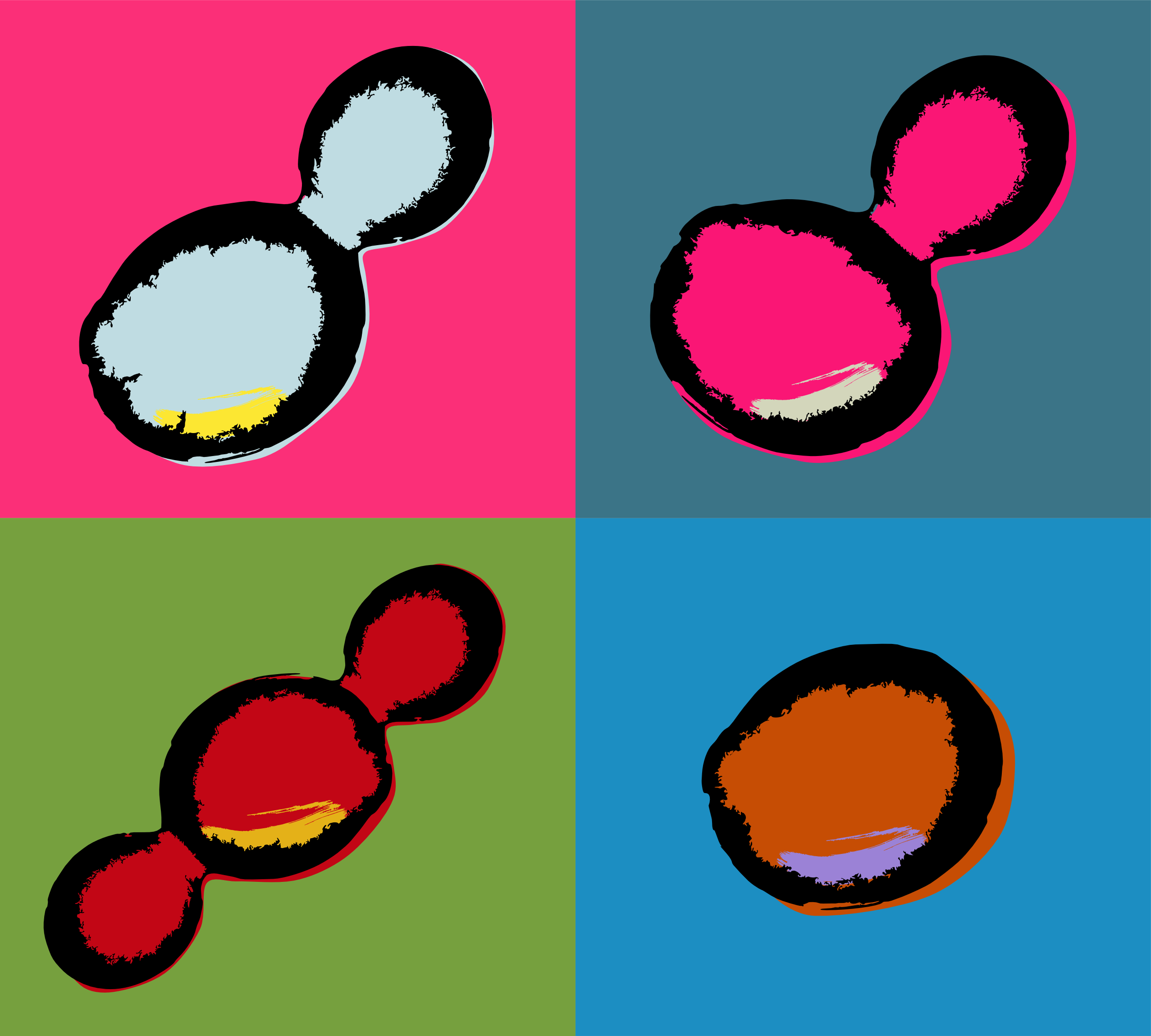

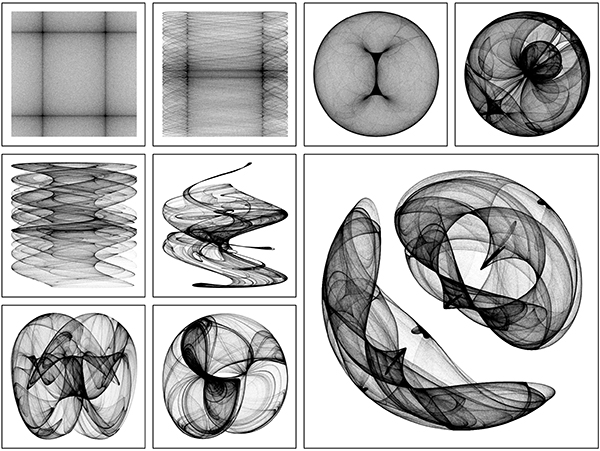

Like the fungi he studies, Steenwyk’s art takes a variety of forms. He has written computer algorithms to generate surreal line drawings and segmented photos called “glitch art”. Other pieces—such as his Andy Warhol-style Portrait of Yeast and his graphic design work for the Rokas Lab and Vanderbilt Evolutionary Studies Initiative—show a direct connection to his scientific studies. Recently, he created a series of portraits to help draw attention to the falling populations of endangered animals.

Whatever the subject or the method, Steenwyk loves art’s power to connect. “Art has enabled me to build bridges between otherwise disconnected groups of people,” he said. He’s noticed that artists and scientists will often stand side-by-side in front of his work at art shows. “The scientists will tell the artists why they think the piece is cool, and the artists will tell the scientists why they think the piece is cool. The scientists walk away with a wider understanding of the world, and the artists walk away with a better grasp on how science affects their daily lives.”

Antonis Rokas, who is Steenwyk’s Ph.D. adviser as well as his lab mentor, shares Steenwyk’s drive to forge connections between people who might not otherwise meet. This focus helped earn the duo a 2019 James H. Gilliam Fellowship from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, which awards $50,000 per year to mentor-student pairs who demonstrate a commitment to diversity. In addition to research support, the program provides intensive training to help both mentors and students learn inclusive leadership. Steenwyk, whose mother is of Filipino, Chinese, Spanish, and Malay heritage, said the program has cemented his desire to pursue a career in academia, in part so he can help create a welcoming environment for fellow researchers from underrepresented groups.

He also wants to help future generations of students see beyond traditional subject-matter boundaries. “People told me that art and science don’t mix, that I had to choose one and become an expert,” Steenwyk said. “But I want to encourage students to understand their core values and let those values guide you and keep you grounded. Stay true to who you are.”