College of Arts and Science Faculty Fight COVID-19 in Latin America

Vanderbilt’s College of Arts and Science has long had connections to Latin America. Through the Center for Latin American Studies, the work of Latin American specialists in departments such as history and anthropology, and numerous student and faculty research trips, the college has forged strong ties to the region, its universities, and its people. So as the novel coronavirus began to spread around the world, some Arts and Science faculty turned their attention south, to see how they could help communities and colleagues in Latin America.

Associate Professor of Anthropology Norbert Ross has worked for the last several years in El Salvador conducting research on how children are affected and cope with violence in their environment. One of the focal areas is a neighborhood just outside the El Salvadoran capital of San Salvador. The neighborhood is one of the poorest in the area, with homes constructed from salvaged materials and virtually no public infrastructure. Ross’s research, funded by a Fulbright Fellowship and an ongoing National Science Foundation (NSF) grant, focuses on how the area’s rampant gang violence affects local children. He conducts art- and theatre-based interventions to help the children process their experiences and tracks health, educational, and other outcomes. He also used his own money and private donations to build and run a community center, which provides the children with academic enrichment and extracurricular alternatives to gang involvement.

When the coronavirus reached El Salvador, the nation’s government imposed a stringent lockdown that has been effective in slowing the spread of the virus but has pushed poor families to the brink of starvation. Anyone who goes outside is subject to arrest and heavy fines, unless they can prove they are collecting water, purchasing food, or obtaining medical care. The families Ross works with are part of San Salvador’s informal economy, so the restrictions have completely eliminated their ability to earn income. And the national census does not count them or recognize their neighborhood, so they are not eligible for government aid.

“For the families I work with, the worry about getting infected [with coronavirus] is less sickening than the worry about not being able to feed their children. I receive phone calls every day from crying mothers, and it is heart-wrenching to listen to their stories. I couldn’t just wait and do nothing,” Ross said.

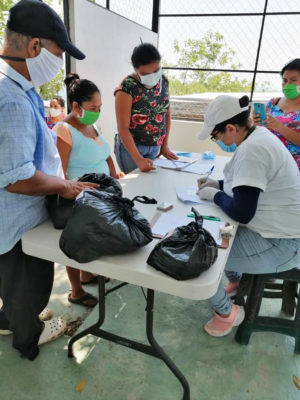

He decided to start a GoFundMe to help feed the roughly 700 individuals (about 200 families) living in the neighborhood, with the community center serving as an orderly distribution point. So far, he has raised money for 3 tons of food for the families. He was also able to obtain help from a local mayor’s office, which provides a police escort and transportation each time the community center’s teacher ventures out to buy food.

Ross intends to continue raising money through GoFundMe and arranging food distributions as long as San Salvador’s lockdown lasts. He is also applying for an additional NSF grant to help him study how structural violence affects people in times of pandemic or other crises. He hopes to uncover the true toll of such events by highlighting their indirect effects, including adverse health outcomes and deaths caused by starvation and elevated levels of violence.

“This has taught me that we’re all in the same storm, but we’re sitting in different boats,” Ross said. “It’s helped me understand a lot of the structural underpinnings of the violence I was already studying. It makes much more visible the vulnerability of certain sectors of the population.”

Associate Professor of Earth and Environmental Sciences Jonathan Gilligan has also pivoted from his usual activities to help with Latin America’s fight against COVID. A specialist in interactions between human society and the environment, Gilligan often collaborates with sociologists and psychologists to study why people make certain choices related to climate change, as well as how they react and adapt to environmental stress. In some of his research, he uses computational modeling to calculate how people’s individual choices add up to affect society as a whole.

(Jenny Mandeville/Vanderbilt University)

“It’s called agent-based modeling, and you can also apply it to animals: how birds form flocks or fish form schools. It’s very applicable to the spread of epidemics because it can model how people spread a disease by interacting with others in their social networks,” Gilligan said.

One of Gilligan’s graduate students, the son of a Colombian epidemiologist, recognized agent-based modeling’s potential to fight the spread of COVID-19. He shared Gilligan’s work with his father, who in turn told his colleagues about it and contacted Gilligan for help.

Gilligan and his lab started by customizing their agent-based model for the Colombian situation. A first version made accurate calculations but was extremely slow. Gilligan was able to revise the model to make calculations for millions of people, and he and the Colombian epidemiologists are now calibrating it using real-life contact data.

The group is using the model to investigate some of the Colombian epidemiologists’ most interesting findings. Most Colombian infections appear to have started with people who were working abroad and brought the disease home with them. The disease then spread along their social networks—but not necessarily in the way Gilligan and his collaborators expected. In particular, they have found that occupation may be more important than number of contacts, since people who intersect with the health care system appear to spread COVID at the highest rate.

Ultimately, Gilligan believes that his model will prove useful on two fronts. First, it can help Colombian epidemiologists predict the locations of COVID outbreaks, so they can shore up resources in advance and prevent local health care systems from becoming overwhelmed. Second, they can use the model to test possible interventions, such as varying degrees of social isolation, and determine which are mostly likely to slow the spread of COVID

Two weeks after Gilligan began working with the Colombian epidemiologists, Vanderbilt University Medical Center contacted him about adapting his model for Tennessee. He also started discussing possible projects with colleagues in the university’s Data Science Institute and the Department of Psychology. The research could explore synergies between Gilligan’s models, artificial intelligence, and neuroscience modeling, with results used to develop solutions for fighting future pandemics. All these projects, he says, are excellent examples of how his position in the College of Arts and Science enables world-changing interdisciplinary work.

“I don’t have a background in epidemiology at all. I couldn’t contribute to the pandemic fight if I didn’t have the opportunity to work with experts outside my field,” Gilligan said. “In turn, I can share what I know about modeling—each person can share information and say, ‘I don’t know about this. Can you explain it to me?’ This is where Vanderbilt’s support for interdisciplinary work is really helpful. It’s critical.”

Visit Norbert Ross’s GoFundMe page to donate to food relief efforts for the families participating in his research.